ALASDAIR WHITTLE, FRANCES HEALY & ALEX BAYLISS. Gathering time: dating the Early Neolithic enclosures of southern Britain and Ireland. xxxviii+992 pages, 640 illustrations, 107 tables, 2 volumes. 2011. Oxford: Oxbow; 978-1-84217-425-8 hardback £45.

Review by Alison Sheridan

National Museums Scotland, Edinburgh, UK

(Email: a.sheridan@nms.ac.uk)

George Box's aphorism, "All models are wrong, some models are useful", offers an apt introduction to this magnificent 992-page, two-volume magnum opus. The fruits of a major Arts and Humanities Research Council- and English Heritage-funded research project, Gathering Time sets out to place the dating of Early Neolithic causewayed enclosures in southern Britain and Ireland on a firmer footing, and to situate these monuments within the broader context of the Early Neolithic in these islands. In doing so, it treats the reader to an in-depth critical evaluation of the currently-available direct dating evidence for all elements of the phenomena that fall within our description of 'Neolithic' (domesticated animals, pottery, etc.), together with a lengthy and wide-ranging reflection on what the authors refer to (p. 1) as "the initial establishment and spread of Neolithic things and practices", as well as a discussion of what happened next. In short, it offers everything you ever wanted to know about causewayed enclosures, and a whole lot more.

This is no bedtime reading, unless the only cure for insomnia is the perusal of endless (but invaluable) lists and tables of radiocarbon dates. Nor is it designed to be read from cover to cover, as this reviewer did, emerging dazed, full of admiration for the sheer scale of the authors' achievement, and occasionally (and predictably) infuriated as regards their broadest-level narrative.

Indeed, such is the level of detail provided in the region-by-region descriptive chapters (Chapters 3–12) that, on page vii, the authors wisely recommend that readers start with the introductory chapters (1 and 2) and one or more of the regional chapters (with the "most digestible" suggested as 3, 7 and 10) before tackling the more synthetic discussions in Chapters 12 and 14 and the grand narrational finale in Chapter 15.

Chapter 1 sets out, with admirable clarity, the background to the project and the aims and structure of the volumes. A brief review of prehistorians' approaches to time and matters of chronological resolution is presented, and the need to get away from 'fuzzy' chronologies, based on eyeballing radiocarbon dates, is emphasised. Chapter 2 deals with radiocarbon dating, and specifically with the use of Bayesian modelling in order to constrain the inherent scatter in dates and to create finer-resolution chronological narratives. The publication deals with 2350 dates, of which 427 were obtained for the project — a major addition to our knowledge base. The issues involved in dealing with old dates, determined on a variety of materials by various laboratories over the past 60 years, are discussed and the rationale and protocols relating to the newly-obtained dates are presented. Interestingly, burnt-on organic residues inside pots were found to produce dates of variable reliability; the reasons for this are currently being explored through English Heritage-funded research at Bristol University. The authors present a model of good practice in sample selection and Bayesian modelling, and they are careful to acknowledge the limitations of the Bayesian approach, chief among which is the necessity to define an end point to the phenomenon being modelled.

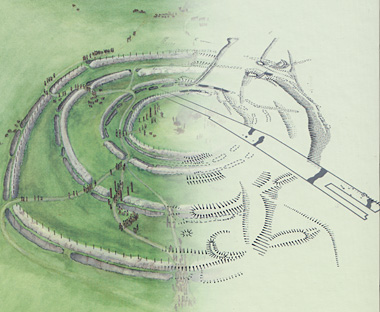

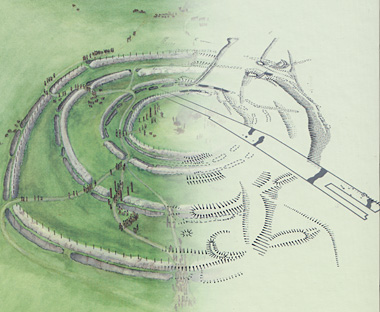

The regional chapters present a systematic account of around 40 causewayed (and tor) enclosures, drawing on advice from excavators and others with in-depth knowledge. For each site, location, topography, history of investigation and previous dating are summarised, and those dates are modelled. The objectives and sampling strategy of the new dating programme for each site are then set out. The results are tabulated, and their analysis and interpretation are discussed before an interpretative chronology (site biography) is constructed. Where alternative models had been proposed, the account describes the 'sensitivity analyses' undertaken to determine best fit. Finally, the implications of the new and modelled dates are discussed. Each chapter ends with a consideration of the causewayed enclosures in the light of other evidence for Early Neolithic activity in the area. Chapter 13 then offers a brief excursus on the carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analyses of human and animal bones from causewayed enclosures, which (inter alia) confirm once more that marine resources did not feature in people's diets at this time; instead, there was a high proportion of animal protein.

The real task of synthesis begins in Chapter 14, where it is concluded that—with the possible exception of Magheraboy in north-west Ireland—causewayed enclosure construction did not constitute the earliest evidence for Neolithic presence in southern Britain and Ireland, but started instead during the last quarter of the 38th century BC (p. 690), several generations after the initial appearance of "Neolithic things and practices" in Britain. Its westward and northward spread from the Thames estuary is posited (fig. 14.16), and while some sites were used only for a short time, others, such as Hambledon Hill, were used for much longer. Their use is discussed, and the incidence of violent conflict is mapped (fig. 14.37). Situating these monuments within the context of other Early Neolithic activity, the authors argue that the earliest evidence for Neolithic "things and practices"—apart from the significantly earlier cattle bones from Ferriter's Cove in south-west Ireland—dates to 4315–3985 cal BC (modelled at 95% probability), and that there had been a spread westwards and northwards from Kent and the Thames Estuary (fig. 14.48), accelerating around 3800 BC (fig. 14.177). Chapter 15 then reviews existing models for the Neolithisation process and posits its own. This features very small-scale cross-Channel movement of farming groups to south-east England, especially the Greater Thames Estuary, during the 41st century BC (and possibly continuing as late as the 38th century), followed by "chain migration" westwards and northwards, which picked up speed around 3800 BC; some diversification of practices and material culture during this process of "chain migration" is used to explain the observed geographical variation. A process of acculturation of indigenous Mesolithic communities is envisaged from the earliest appearance of the colonists, as is continuing contact with the Continental source area/s (which is invoked to help explain why people in southern Britain subsequently started to construct causewayed enclosures). The authors are studiedly vague about the location of the source area/s (except in the case of fig. 15.8, of which more anon) and the reasons for the putative colonisation.

While the volumes provide a wonderful panorama of information about many parts of Britain and Ireland, indeed essential for all who are interested in the Early Neolithic, serious points of contention remain. From this reviewer's perspective, their dismissal of her 'Atlantic façade, Breton' strand of Neolithisation (Sheridan 2010: 92–5), and their argument that passage tombs in Ireland did not start to be built until the third quarter of the fourth millennium BC (p. 657), is wholly unconvincing. Their refusal to acknowledge that the type of monument represented at Achnacreebeag and elsewhere along the Atlantic façade of Britain and Ireland, and its pottery, are distinctly different from the monuments and material culture of the Carinated Bowl Neolithic (p. 850), being instead relatable to Morbihannais traditions is, frankly, perverse. Just because neither Audrey Henshall nor Graham Ritchie regarded the closed chamber and simple passage tomb at Achnacreebeag as warranting exceptional attention does not mean that it does notstand at the beginning of a long and complex sequence of passage tomb development in Scotland. Furthermore, in seeking to situate its late Castellic pottery within the later ceramic repertoire of Scottish court tombs and Irish mid-fourth millennium traditions, they deny and indeed invert the very clear stylistic evolution of this specific kind of pottery set out by this reviewer back in 2003 (and indeed as long ago as 1985)! The fact that, as early as 1975, Gérard Bailloud had remarked on the striking similarity of the Achnacreebeag bipartite bowl to Castellic pottery is not remarked upon; and in focusing on the modelled end-point of late Castellic pottery use in the Morbihan, rather than on its overall modelled currency (Cassen et al. 2009: 761, fig. 13), they try to shoehorn Achnacreebeag and its British and Irish comparanda into a post-39th century BC scenario. And with the Irish comparanda, they rightly cast doubt on Burenhult's early dates for the Carrowmore cemetery, but throw the baby out with the bathwater: a more thorough evaluation of the Carrowmore dates by Stefan Bergh has arrived at a different conclusion (Bergh & Hensey forthcoming). Indeed, the rationale for placing the start of Irish passage tombs as late as 3640–3205 cal BC (p. 657) is based partly on the exigencies of the Bayesian modelling method, which demands that an end be defined for the phenomenon being modelled (here, the Irish Early Neolithic). On the grounds that the construction of passage tombs and the use of the associated material culture in Ireland represents a change from what this reviewer terms 'Carinated Bowl Neolithic' practices and material culture, the authors use this as a defining characteristic for "a meaningfully constituted middle Neolithic" (p. 633). This, surely, represents special pleading and an unsettling circularity of argument.

The authors fare little better in critiquing this reviewer's 'trans-Manche ouest' strand of Neolithisation (Sheridan 2010: 99–101; 2011 and Sheridan et al. 2008). They mistakenly lump the Broadsands simple passage tomb into the 'Atlantic façade' strand (p. 808) and, even worse, wrongly describe its pottery as belonging to the Carinated Bowl tradition (p. 852), despite this author's careful argumentation to the contrary in the aforementioned publications. This, and other errors (e.g. regarding the status of the Er Grah cattle [p. 849; cf. Cassen et al. 2009: 739], of the Ferriter's Cove sheep tooth, and of the nature and development of Carinated Bowl pottery in Scotland) vitiate an otherwise worthy—if over-long—discussion of Neolithisation. Finally, the inclusion of figure 15.8 (on p. 869 and on the back cover of Volume 2), which suggests multi-strand colonisation from different parts of France, is at odds with the model of 'ex-SE England lux' argued elsewhere (e.g. fig. 14.177) and demands more explanation than the authors provide.