Technological challenges on the Limes Transalutanus

The Kingdom of Dacia—comprising the central and western territory of modern Romania—was conquered by the Emperor Trajan at the peak of the Roman empire’s military power in two wars during AD 101–102 and 105–106 (see Oltean 2007: 54–55). This conquest came at a price, for Trajan had broken the tradition established 100 years earlier by Augustus of aligning the empire’s borders with natural frontiers such as the Rhine or Danube. A new research project entitled ‘Interdisciplinary technology for archaeological field survey. Case study—Limes Transalutanus south of Argeş River’ commenced in July 2014, with the aim of researching one section of Rome’s new land frontier in Dacia.

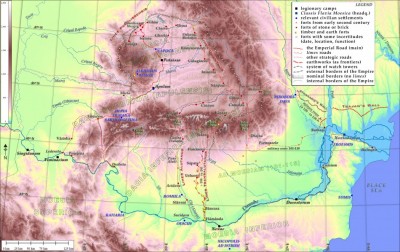

Common opinion about the strategic error of Trajan’s conquest—that is, giving up the protective line of the Danube for a long and difficult land frontier—is only half true; the frontier was indeed long, but it was not so challenging to retain. Figure 1 illustrates the layout of the Roman frontier section under study, integrated within the Roman defensive system established around Dacia and across the region of the Lower Danube. It is clear that, during the second century AD, most of the frontier was located along mountain chains, with few, militarily usable passes and completed by long, fluvial frontiers along the lower courses of the Mureş and Tisza rivers, and also the river Olt (Alutus).

The natural defence offered by the Carpathian Mountains was augmented by military works on the north-western border of Dacia only, extending for about 6km, in order to close the access route to Porolissum. As a general rule, the major forts of the limes were built in valleys, while the surrounding higher land was thoroughly controlled from watch towers—an arrangement already established for a 42km line south-west of Porolissum (Gudea 1997).

The only other frontier of this region defended by extensive works was the Limes Transalutanus, on the south-eastern fringes of Roman Dacia (Napoli 1997: 322–35). It was constructed during the late second century, although not as a ‘double limes’—making a pair with the Limes Alutanus—as it is usually assumed, but rather as a shorter communication route to south-eastern Transylvania. All Roman defence in eastern Dacia was connected by one vital point: the fort at Breţcu (Angustia), which blocked the vulnerable Oituz Pass. Angustia was as important for eastern Dacia as Porolissum was for the western half of the province. Unfortunately, it was at considerable distantance from the so-called Imperial Road that was the backbone of the Roman communication system, connecting Drobeta (on the Danube) and Porolissum via Tibiscum, Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, Apulum, Potaissa and Napoca. No section of this road was closer than 200km (as the crow flies) from Angustia. The main routes for supplying this strategic fort from the eastern frontier collapsed one after another (see Figure 1), and the remaining route, along the Alutus, was excruciatingly long (472km). This is why the new frontier—the Limes Transalutanus—was needed, shortening the line of communication by almost 30 per cent.

Although well known since the late nineteenth century (Tocilescu 1900), especially through excavation of associated forts, the current state of research for this section of the limes is relatively poor. For instance, only one watch tower has been investigated archaeologically (Bogdan Cătăniciu 1977, 343–44), and only three others have established locations. In a recent book, present author Eugen S. Teodor (2013: 23–24, 137–38) shows that the related towers were far more numerous and that their modulation along the limes was similar to other, better-known frontiers.

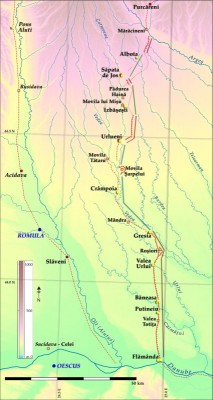

Nonetheless, the Limes Transalutanus exhibits some peculiar features. Along its southern section, the frontier ran 55km across country and was marked by a continuous vallum, or bank and ditch (Figure 2); the central section was a typical ripa, or river frontier, extending 40km and protected by the high terraces of the Vedea and Cotmeana rivers; the northern section (south of the Argeş River, which is the limit of the current study area) again followed a cross-country route, extending 57km, although in this section, the embankment was discontinuous. (For the terminology of Roman frontiers, see Isaac 1988: esp. 125–33.) The form of the latter, northern section suggests two potential explanations: the wall has been completely flattened by agriculture, making it invisible; or, the artificial obstacle never existed, probably because it was unnecessary as the border was naturally defined by forest and swamps that no longer survive. Another peculiar feature of this section of the limes is that for more than a century it was known by Romanian archaeologists as a ‘wall without a ditch’ (see Napoli 1997: 12, 39–41), but the absence of a ditch seems difficult to explain for an earthwork that comprises 19m3 of soil for each linear metre of bank.

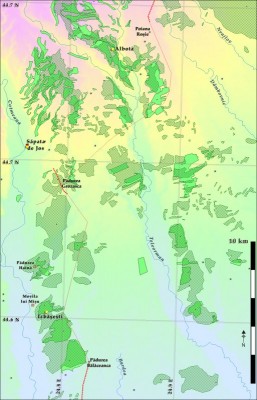

In order to explore these issues, the current project will put particular focus on toponymy, or place names (Figure 3). This is a practical solution for a country where the oldest-available detailed maps date from the mid nineteenth century (Szathmáry Map, 1:28 000). The project also uses new research technologies and approaches. An explicit goal of the project is to test and find the optimal balance between the cost, time and efficiency of investigations, bearing in mind the linear nature of the monument—a typical experience for archaeological projects in advance of transport infrastructure developments. A large set of resources and techniques will be tested both as alternative and complementary tools. For example, we will systematically use all available digital data, such as digital elevation models (DEMs), orthophotos, photographs taken from aeroplanes (both vertical and oblique, from about 700m altitude) and UAVs (250–400m, see Figure 4). These remotely sensed data will be used to plan fieldwork, including systematic and linear field-walking, geophysical survey (including from UAVs), topography (complementary to DEMs acquired using UAVs), geological core drillings, pedological and palynological sampling, and test excavations.

As part of the project, we are organising an international symposium to be held in May 2016 entitled: ‘Old frontiers, new technologies: an evaluation of costs and opportunities in field archaeology’. Potential contributors should contact the authors for further details.

Acknowledgements

The project is funded by UEFISCDI, the executive unit for research of the Romanian Ministry of Education (http://uefiscdi.gov.ro), contract no. 317/2014.

References

- BOGDAN CĂTĂNICIU, I. 1977. Nouvelles recherches sur le Limes du sud-est de la Dacie, in J. Fitz (ed.) Limes: Akten des XI internationalen Limeskongresses Székesfehérvár 1976: 333–54. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

- GUDEA, N. 1997. Der Meseş-Limes. Die vorgeschrobene Kleinfestungen auf dem westlichen Abschnitt des Limes der Provinz Dacia Porolissensis. Zalău: County Museum Sălaj.

- ISAAC, B. 1988. The meaning of the terms Limes and Limitanei. Journal of Roman Studies 78: 125–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/301454

- NAPOLI, J. 1997. Recherches sur les fortifications linéares romaines (Collection EFRA 229). Rome: École française de Rome.

- OLTEAN, I. 2007. Dacia. Landscape, colonisation and romanisation. London & New York: Routledge.

- TEODOR, E.S. 2013. Uriaşul invizibil: Limes Transalutanus. O reevaluare la sud de râul Argeş. Târgovişte: Editura Cetatea de Scaun.

- TOCILESCU, G.G. 1900. Fouilles et recherches archéologiques en Roumanie. Communications faités à l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belle Lettres de Paris, 1892–1899. Bucharest: Imprimerie du Corps didactique.

Authors

* Author for correspondence.

- Eugen S. Teodor *

Archaeologist, Computing Department, Romanian National History Museum, Calea Victoriei 12, Sector 3, Bucharest, RO-030026, Romania (Email: esteo60@yahoo.co.uk) - Dan Ştefan

Vector Studio, Garibaldi 5, Scara C, Apartment 23, Bucharest, RO-020221, Romania (Email: danstefan00@gmail.com)

Cite this article

Cite this article