Digital recolourisation and the effects of light on Neo-Assyrian reliefs

This paper is based on a Gold Medal prize-winning dissertation from the 2015 international Undergraduate Awards competition (http://www.undergraduateawards.com). Li Sou’s dissertation on Neo-Assyrian reliefs topped the ‘Classical Studies and Archaeology’ category, one of 25 disciplines for which prizes are annually awarded.

Introduction

This paper presents the results of an investigation into the use of colour on Neo-Assyrian relief carvings. Additionally, the effects of lighting angles on these reliefs are also considered in order to demonstrate the variety of details highlighted under different conditions. Gypsum relief carvings originally decorated the palaces of the Neo-Assyrian Empire between the ninth and seventh centuries BC, often depicting scenes of royal prowess and military victory (Ataç 2010). Although reliefs were originally painted with various pigments, much of the colour has been lost due to weathering, poor preservation and exposure to light and moisture (Layard 1849: 130).

While the use of colour has been recognised (e.g. Cohen & Kangas 2010), few pigments have been subject to analysis (but see Verri et al. 2009), and a limited number of colour schemes have been reconstructed. Yet the original polychrome appearance of the reliefs would have been dramatically different from their present monochrome condition, suggesting alternative experiences and meanings. This research therefore aims to consider which colours were most frequently used, which features were most often painted and whether there was variation in the use of colour over time.

Methodology

To establish a baseline for the reconstruction of colour, evidence for surviving pigments on reliefs was collected. A representative sample was identified, which focused on reliefs originally located in the north-west palace of Ashurnasirpal II (reigned 883–859 BC) at Nimrud and the palace of Sargon II (reigned 721–705 BC) at Khorsabad. This provided the opportunity to analyse changes in colour schemes from the reigns of the two kings. Data was collected by direct visual analysis and through enquiries to curators from the British Museum, the Fitzpatrick Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Details of visible colour on reliefs within museum collections were recorded, including pigment colour and the location of painted details. Additionally, sketches, drawings and written accounts by nineteenth-century excavators were also consulted.

Evidence of colour on painted wall friezes and glazed bricks from Neo-Assyrian palatial sites was also compiled for comparison. These decorative elements were located above relief panels on the walls at both Nimrud and Khorsabad (Reade 1995: 227), although it should be noted that reliefs and glazed brick murals and wall paintings were not always found in association. Both datasets are used to inform the reconstructed colour schemes.

Results and reconstructions

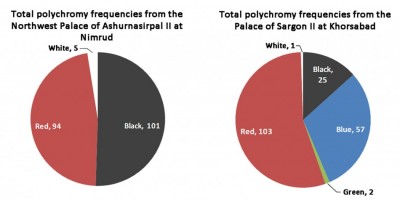

Surviving evidence of colour use from the north-west palace of Ashurnasirpal II is limited to a palette of black, white and red. Traces of red are sometimes found on features such as bows, the bases of sandals and on headwear and jewellery (Figure 1). Such colourations are mostly naturalistic and used particularly to highlight facial features, with hair, beards, eye outlines and pupils painted black, whereas white pigment is noted for the whites of the eyes. This standardised scheme is found on all surviving painted reliefs from Ashurnasirpal II’s north-west palace, and therefore features in all versions of the reconstruction (Figure 2).

It is possible that red was selected as the closest available colour pigment to depict wood, on objects such as bows and staves, while the choice of red for jewellery could reflect the Akkadian term of ‘red gold’ used to describe a specific shade of the precious metal (Reiner et al. 1984). Pigments survive particularly well on the footwear of relief figures, and it is possible that preservation conditions for colour were more favourable on the base of the carvings. This standardised colour scheme is observed on all surviving painted sandals, with a red trim and black central panel and laces.

Figure 3 shows that blue is the predominant pigment used on reliefs from the palace of Sargon II at Khorsabad, in contrast to the abundance of black pigment surviving on reliefs from the north-west palace (Figure 3). Additionally, it was found that Sargon’s sandals were painted differently to those of other figures, which were decorated with blue and red stripes, marking him out as different in comparison to the plain sandals of courtiers, soldiers and others (Figure 4).

The importance of blue in the colour palette of Sargon II’s palatial reliefs may be connected to the high value attributed to this colour through its association with lapis lazuli, which was particularly valued in Neo-Assyrian culture (Moorey 1994: 85). As such, the extensive use of blue on reliefs of this date may reflect the intention to convey prestige and wealth, particularly as it was used for features such as metal weapons and armour (Figure 5).

It is clear from the reconstructions that the use of colour on these reliefs creates a striking effect, highlighting and distinguishing certain features (Figure 6). In the case of Sargon II, his unique sandal colour scheme reflects an intention to differentiate him from other human figures. The addition of colour to natural features such as hair and eyes creates a more lively appearance, potentially distinguishing Assyrians from other races shown on the reliefs. No traces of pigment were found on any of the figures’ skin, nor in the backgrounds. It is uncertain on the basis of surviving archaeological and textual information whether the reliefs were originally fully coloured.

Examining the effects of light

An experimental reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) model was developed to test how different lighting angles cast light and shadow over a Neo-Assyrian relief from the north palace of Ashurbanipal (reigned 668–631 BC) (DUROM.1950.4, Oriental Museum, Durham). This provides a controllable method for assessing the variable clarity of the details on the relief.

Figure 6 clearly shows that the relief was not intended to be viewed from an adjacent light source, as the intricate detail is washed out. While lighting from above and below casts somewhat better shadows, the optimum lighting directions were found to be from oblique angles to the left or right, casting shadows of the greatest depth. Specific image details are highlighted as light moves horizontally past the relief; this suggests that a handheld light source may have been the intended means of illumination, carried by a person walking through the palace complex.

Conclusions

Polychromy was used on select parts of Neo-Assyrian reliefs, allowing specific features to be highlighted; for example, martial gear, human features and costume. The possibility that pigments may have been used on background areas or on other relief features, however, is not ruled out. Additionally, it was found that standardised colour schemes were used at the two palaces, although the schemes are not identical. It is clear that a substantial amount of colour pigment survives, and it is probable that inspections of other reliefs will reveal more traces than hitherto recognised. The position and angle of light also has a strong effect on the visibility of particular features. These results suggest that further research into the use and effects of light and colour on Neo-Assyrian reliefs would be worthwhile.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are owed to: Nigel Tallis and St John Simpson for permission to study the British Museum reliefs; Jennifer Marchant at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, and the Trustees of the British Museum for permission to reproduce photographs; and the Oriental Museum, Durham, for permission to analyse reliefs. Research visits were funded by the Rosemary Cramp Fund, Durham University. I am grateful to Graham Philip for his supervision, and to Jeff Veitch for his help in calibrating colours and creating the RTI imagery.

References

- ATAÇ, M. 2010. The mythology of kingship in Neo-Assyrian art. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- COHEN, A. & S.E. KANGAS (ed.). 2010. Assyrian reliefs from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II: a cultural biography. Hanover (NH): University Press of New England.

- LAYARD, A.H. 1849. Nineveh and its remains. London: John Murray.

- MOOREY, P.R.S. 1994. Ancient Mesopotamian materials and industries: the archaeological evidence. Oxford: Clarendon.

- READE, J.E. 1995. The Khorsabad glazed bricks and their symbolism, in A. Caubet (ed.) Khorsabad, le palais de Sargon II, roi d’Assyrie: 225–36. Paris: La Documentation Française.

- REINER, E., R.D. BIGGS, R.I. CAPLICE, M.B. ROWTON, P.T. DANIELS & J. ROBINSON (ed.). 1984. The Assyrian dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Volume S. Chicago (IL): Oriental Institute.

- VERRI, G., P. COLLINS, J. AMBERS, T. SWEEK & S. SIMPSON. 2009. Assyrian colours: pigments on a Neo-Assyrian relief of a parade horse. The British Museum Technical Research Bulletin 3: 57–62.

Author

* Author for correspondence.

- Li Sou*

Department of Archaeology, Durham University, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, UK (Email: li_sou@hotmail.co.uk)

Cite this article

Cite this article