Daily life in ancient Sagalassos

Introduction

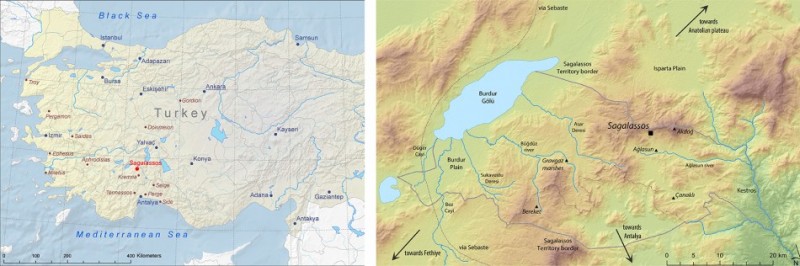

During the 2014 summer archaeological campaign of the University of Leuven (Belgium) in ancient Sagalassos (Burdur Province, Turkey), unique contexts were excavated that bear direct witness to the daily life of the past in this Roman imperial town (Figure 1).

The Sagalassos Archaeological Research Project is headed by Professor Dr Jeroen Poblome, who took over from Professor Dr Emeritus Marc Waelkens earlier this year (Poblome 2013). This summer, the research team has engaged with a number of new themes, in addition to continuing with the established interdisciplinary research strategy of the Sagalassos Project, including its attention to the conservation and restoration of a range of ancient monuments (Figure 2).

One of the new research topics is the study of aspects of the daily life of the community of Roman imperial to Early Byzantine Sagalassos (end of the first century BC to seventh century AD). Important discoveries were made in this respect within two excavation areas.

A communal feast

The first excavation is situated in the Eastern Suburbium, an area of about 6ha, forming a very busy district of the Roman town. The area includes an extensive necropolis, and the only road allowing heavy traffic into Sagalassos passes through this quarter. Clay was quarried in various places and many small stone quarries were in operation; there was also metal-working and pottery production. In the Early Christian period, a church towered over this urban quarter.

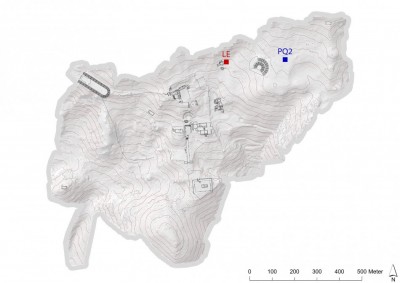

Next to a crossroads in the western part of the suburb, the team from the University of Leuven investigated a large, rectangular building (c. 11.5m × 14.5m, Figure 3). The thick, mortared stone walls, including recycled ashlar blocks, were identified during preliminary geophysical research. The building was first erected during the late first century BC/early first century AD, and it remained in use for a number of centuries. Access was provided through wide doors in the front and back walls and, in the middle of the building, a rectangular water feature was installed; it is unclear how the building was roofed. After some years of use, the water feature was removed and the original, single-interior space was subdivided into rooms. In three of these rooms enormous quantities of archaeological material were found, as though it was left only yesterday; in fact, they date to c. AD 200. The finds include objects made of materials such as metal and carved bone, as well as glass flasks and drinking cups, oil lamps and large quantities of ceramic tableware (Figure 4). Many of the latter, especially bowls and dishes, were preserved intact and discovered upside down, containing original food remains. These finds seem to relate to ancient communal dining practices involving dozens of participants. The tableware and food remains were not tidied away, but rather thrown along the walls of the building and left behind; this was a one-off event, not resulting from accumulation. Indeed, from the waste patterns in other parts of the building, there were more such events, yet the function of the building seems to be related to communal dining, so the building was not abandoned after this; instead, they remodelled the floor and continued happily wasting.

As well as the study of the artefacts, an interdisciplinary team from the Leuven Center for Archaeological Sciences has initiated research into the food remains, including the animal bone and carbonised plant and fruit remains, with the aim of reconstructing the ancient menu. The nature of the building and the practice of communal dining permit us to hypothesise the presence of a convention hall, where an association, such as an artisanal guild or a religious or social group, gathered. Associations were a very common feature of social life in antiquity and, although these institutions are fairly well documented by inscriptions (including at Sagalassos), as well as papyri, no such building has yet been previously excavated in Turkey. Aside from the fact that undisturbed primary deposits are very rare in the archaeology of Sagalassos, this excavation reveals important new knowledge on the customs and practices of ancient associations in Roman provincial towns.

A Byzantine cooking set

The second discovery is also new to the archaeology of Roman Asia Minor: the excavation of a completely preserved cooking set dating to the sixth century AD. The stove and the remains of the small kitchen, which it formed part of, were installed into an abandoned potters’ workshop. The site is adjacent to the so-called Neon-library of Sagalassos, along one of the main streets in the upper town connecting the Upper Agora with the theatre (Uleners & Poblome 2014; Figure 5).

The kitchen is small and the cooking set is positioned low to the ground, providing poor ergonomics (Figure 6). The floor of the kitchen unit was of beaten earth. The cooking set was a simple construction of brick and tile fixed in mud plaster and framed with heavy cornerstones. One central stokehole provided heat to three depressions in the top of the set, in which round-bottomed cooking pots could be placed. Prior research has revealed the popularity of porridges and stews in ancient Sagalassos (Poblome 2012). So far, this is the only completely preserved cooking set from Sagalassos and, as far as is known, from Turkey too.

The discoveries made in 2014 enhance the knowledge of ancient cuisine and diet and, in turn, contribute to the sustainable regional development plans that the Leuven team is developing for the Sagalassos region. The traditional regional cuisine, which contains a range of recognisable elements eaten in antiquity, had all but disappeared, but now features once again on the menus of local businesses.

Acknowledgements

The 2014 excavations at Sagalassos were supported by the CORES network of the Belgian Programme on Interuniversity Poles of Attraction (http://iap-cores.be/), the Research Fund of the University of Leuven (GOA 13/04) and Project G.0562.11 of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO). The team is grateful to the Turkish Ministry of Tourism and Culture for its annual research permit.

References

- POBLOME, J. 2012. ‘Our daily bread’ at ancient Sagalassos, in M. Cavalieri (ed.) FERVET OPUS, 1 INDVSTRIA APIVM. L’archéologie: une démarche singulière, des pratiques multiples. Hommages à Raymond Brulet: 81–94. Louvain-la-Neuve: Presses Universitaires de Louvain.

– 2013. Exempli Gratia. Sagalassos, Marc Waelkens and interdisciplinary archaeology. Leuven: Leuven University Press. - ULENERS, H. & J. POBLOME. 2014. A new and unexpected potters’ workshop at Sagalassos. Anmed. News of Archaeology from Anatolia’s Mediterranean Areas 12: 87–93.

Author

- Jeroen Poblome

Department of Archaeology, University of Leuven, Blijde Inkomststraat 21/3314, 3000 Leuven, Belgium (Email: jeroen.poblome@arts.kuleuven.be)

Cite this article

Cite this article