Neolithic pottery production workshop at Ulucak Höyük, western Turkey: evidence for a full production sequence

Introduction

Ulucak Höyük lies 25km east of İzmir in west-central Turkey (Figure 1). The site is not only among the earliest Neolithic settlements in the region, but its well-preserved building sequences also span a period of more than 1000 years (6800–5700 cal BC). Material evidence from Neolithic layers at Ulucak, represented by levels VI–IV, suggests a strong continuity, although with the introduction of some new elements through time.

From c. 6500 cal BC onwards, pottery increasingly became an integral part of life in the Ulucak Neolithic community. The recent discovery, however, of a pottery workshop in Ulucak IVc, dated to 5840–6005 cal BC, represents the first and earliest evidence for such a specialised pottery production area, not only in Ulucak itself, but possibly also in the Near East.

Pottery workshop

The workshop consists of two adjacent, post-framed structures, buildings 55 and 56, both of which were heavily burnt and therefore yielded many in situ artefacts (Figure 2). The building technique of the structures is unusual for the time period, as all the previously excavated buildings belonging to the post-6000 BC horizon at Ulucak were built of substantial sun-dried mudbricks on stone foundations. No direct access between buildings 55 and 56 has yet been found, but their inventories clearly show that they were functionally related. In fact, further excavations may indicate that the workshop was originally a building complex consisting of a number of interconnected rooms, as suggested by two door openings found on the same axis in building 55 (Figure 3). The northern and southern sections of building 55 (covering 16m2) were divided into two working areas by elevated stone-paved and mud-plastered platforms. Two ovens and two accompanying grinding installations were set against the western and southern walls of the structure. Building 56, of which around 10m2 has been uncovered so far, only contains a daub bin.

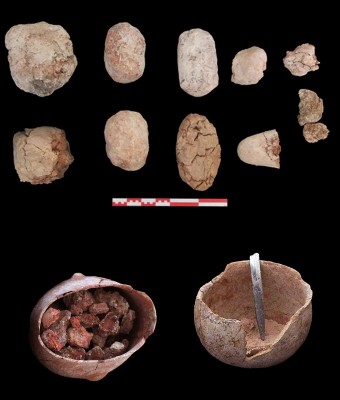

The extraordinary nature of building 55 is further demonstrated by 15 grinding stones—of which six were found in situ on one of the grinding installations—a large stone mortar and three stone pestles. Red pigment is one of the most striking discoveries within the building: as well as almost all the grinding stones, six polishing stones and two clay vessels demonstrate remnants of red pigment that was also found in the form of small lumps scattered in various locations (Figure 4, below). Red pigments possibly originated from the hematite sources that are located around 5km from the site. Both buildings yielded more than a dozen clay loaves. Although these loaves were all burnt, and are therefore well preserved, none of them have exactly the same colour or texture (Figure 4, above). The lower part of an unfinished vessel is possibly the first direct archaeological evidence for the coiling process in pottery manufacturing (Figure 5, left side), although coil building has generally been accepted as a primary technique in Neolithic pottery manufacturing in the Aegean and western Turkey (Eslick 1992; Wijnen 1993; Pyke & Yiouni 1996). Coarse, flat circular plates with various diameters, which are peculiar to the workshop, appear to have been used as a basic tournette during the coiling process according to desired vessel size (Figure 5, right side). The bone-tool assemblage is mainly characterised by points and spatulas (Figure 6). Spatulas may well have been used for the shaping and smoothing of clay during pottery production. A point with red pigment traces found in a ceramic bowl containing red pigment residue, which had been diluted into ‘paint’, may show that points were used for simple processes such as mixing pigment.

There remains little doubt that the assemblage, including clay loaves, an unfinished coiled vessel, unusual circular plates, bone tools, numerous polishing stones and an excessive number of grinding stones, represents what one might expect to find in a specialised pottery production area. As almost 90 per cent of the Neolithic monochrome wares from Ulucak IV are red-slipped burnished wares, the large amount of red pigment in various forms from the buildings is unsurprising.

Implications and ongoing research

Craft specialisation is a longstanding issue in archaeology, generally discussed in the context of the emergence of complex societies (Costin 1991; Schortman & Urban 2004). Production of certain items has also been associated with specialists since at least the ninth millennium BC, although both the obscurity of the criteria provided by theoretical approaches, and the scarcity of archaeological evidence, generally prevent us from tracing these initial specialists in terms of production sequence, its organisation and relations with consumers (Perlès & Vitelli 1999; Twigger 2009; Baysal 2013). Based on the level of skills, technological knowledge and experience evidenced by the pottery, it has generally been suggested that production by specialist potters began after c. 6000 BC in the Aegean (Perlès & Vitelli 1999; Çilingiroğlu 2012). Ongoing excavations at Ulucak, together with further investigation of the assemblages, including petrographic and chemical analysis of a large number of pottery samples undertaken by the Fitch Laboratory of the British School at Athens, will provide the opportunity to enhance understanding of various aspects of Neolithic pottery production during the sixth millennium BC in the Aegean.

Acknowledgements

Support and funding came from the Ministry of Culture Republic of Turkey, Trakya University and the Turkish Science Foundation (TÜBİTAK 114K271); and from private sponsors KOSBİ, Socotab and Elkima. We wish to thank our team: Emma Baysal, Evangelia Pişkin, Adnan Baysal, Jarrad Paul, Evangelia Kiriatzi and Noèmi Müller.

References

- BAYSAL, E. 2013. Will the real specialist please stand up? Characterising early craft specialization, a comparative methodology for Neolithic Anatolia. Documenta Praehistorica 40: 233–46

- ÇİLİNGİROĞLU, Ç. 2012. The Neolithic pottery of Ulucak in Aegean Turkey: organization of production, interregional comparisons and relatice chronology (British Archaeological Reports international series 2426). Oxford: Archaeopress.

- COSTIN, C.L. 1991. Craft specialization: issues in defining, documenting, and explaining the organization of production, in M. Schiffer (ed.) Archaeological method and theory, volume 3: 1–56. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- ESLICK, C. 1992 Elmalı-Karataş I. The Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods: Bağbaşı and other sites. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- PERLÈS, C. & K.D. VITELLI. 1999. Craft specialization in the Neolithic of Greece, in P. Halstead (ed.) Neolithic society in Greece: 96–107. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic.

- PYKE, G. & P. YIOUNI. 1996. Nea Nikomedeia: the excavation of an Early Neolithic village in northern Greece, 1961–1964. London: The British School at Athens.

- SCHORTMAN, E. & P. URBAN. 2004. Modelling the roles of craft production in ancient

- political economies. Journal of Archaeological Research 12: 185–226.

- TWIGGER, E.L. 2009. The question, nature and significance of Neolithic craft specialization in Anatolia. Unpublished PhD dissertation.

- WIJNEN, M.H. 1993. Early ceramics: local manufacture versus widespread distribution. Anatolica XIX: 319–30.

Author

- Özlem Çevik

Department of Archaeology, Trakya University, Balkan Campus, Edirne 22030, Turkey (Email: arkeocevik@gmail.com)

Cite this article

Cite this article