Newly documented domestic architecture at Iron Age Busayra (Jordan): preliminary results from a geophysical survey

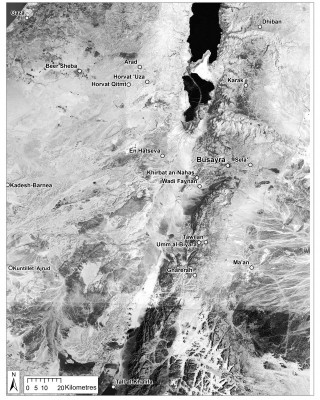

Edom was one of several Levantine territorial polities that emerged during the first half of the first millennium BC (Figure 1). The kingdom’s development, from dispersed semi-nomadic populations to a loosely integrated polity that spanned south-west Jordan and southern Israel, remains a vital area of research. The Busayra Cultural Heritage Project (BCHP) investigates Edom’s political and economic development at Busayra. Excavations during the 1970s documented fortifications, monumental buildings and domestic residences that were occupied between the eighth and fifth centuries BC (Bienkowski 2002). Some buildings demonstrate architectural styles similar to those found in Assyrian monumental buildings in northern Iraq. Written sources concur that the Assyrian and later Babylonian and Achaemenid Empires held intermittent control over Edom and its neighbours, beginning in the eighth century BC. The BCHP investigates the nature and intensity of this colonialism in order to understand how elites and non-elites alike responded to these external stresses on their economic and cultural practices.

One project goal is to measure how, if at all, Edom’s domestic economies were transformed under imperial suzerainty. Excavations at neighbouring settlements have determined that subsistence was based on agro-pastoralism. These villages also contributed to, and participated in, international trade networks that crossed the southern Levant. These buildings, however, were not sampled in a sufficiently rigorous way so as to enable understanding of specific practices and their changes over time. In December 2014 and August 2015, the authors conducted a three-week geophysical survey to identify additional domestic structures at Busayra. With the permission of Jordan’s Department of Antiquities, the team used magnetic gradiometry and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) on approximately 4000m2 of unexcavated ground.

Methods

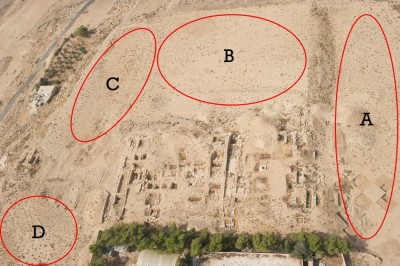

The BCHP subdivided the area into four survey units: A, B, C and D (Figure 2). Both geophysical surveys were conducted with a 50cm transect spacing. The magnetic gradiometry survey was carried out using a Bartington 601-2. It is a single-axis magnetic field gradiometer system comprised of two gradiometers mounted 1m apart. A GSSI SIR-3000 with 400MHz antenna was employed in the GPR survey. This instrument configuration allows a prospecting depth of up to approximately 2m, depending on soil conditions. A total of 400 transects were surveyed across an area of 4000m2.

Results

Excavations at Busayra and neighbouring settlements reveal that domestic architecture was constructed using a repeated rectilinear design, with interior walls dividing the buildings into a series of two or three rooms. The authors used this repeated pattern to identify additional subterranean domestic buildings in two of the four survey units using the images produced from the geophysical data.

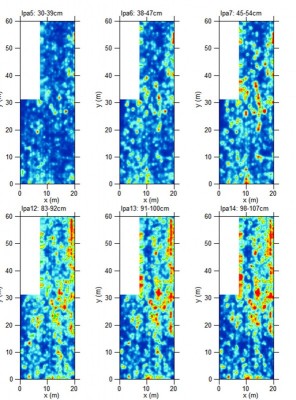

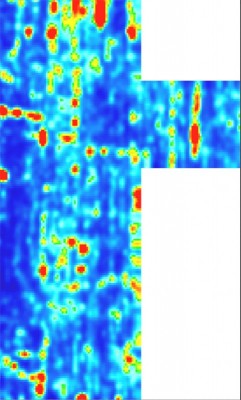

In area C, the magnetic gradiometry data appear void of anomalies in the northern portion, while the southern portion contains a series of regularly spaced, negatively magnetic rectangular anomalies (that appear as light grey to white areas in the data). The interior spaces of these rectangular features are frequently characterised by highly magnetic (dark grey to black) areas. These subterranean, negatively magnetic signatures are consistent with exposed limestone-wall signatures, and indicate buried limestone architecture (Figure 3). The dark interiors are consistent with cultural activity areas with increased magnetism due to the presence of concentrated organic and thermal materials such as charcoal and hearths. These architectural features are adjacent to the domestic structures that were identified by the earlier project (Bienkowski 2002: 137–38). The proximity of this architecture to the previously excavated domestic structures, as well as the presence of what have been interpreted as small, square rooms within long rectangular buildings, suggests that the architecture in the southern portion of area C is also domestic in nature. The GPR data in this area add little to this interpretation but confirm the identification of a few short walls aligned north-east to south-west (Figure 4).

Additional domestic architecture may also be present in survey area D, which is located between the domestic architecture excavated by Bennett in her area B, and in the area C palace (Bienkowski 2002: 199–200) (Figure 5). Although linear anomalies are evident throughout the area, the most dominant architectural feature is a large rectilinear structure in the centre of the image. This structure’s architectural layout appears more grid-like than those of other documented structures. Similar to other areas, the GPR data do not provide additional evidence of anomalies beyond those visible in the magnetometry data (Figure 6). Sampling through excavation will be necessary to confirm whether or not this building did indeed serve a domestic purpose.

Conclusion

These results demonstrate the capacity of geophysical technologies, particularly magnetometry, to identify domestic architecture at Busayra. The refined understanding of the settlement’s layout will permit the authors to excavate targeted rooms that promise to illuminate the economic relationships between households and the Edomite polity before and during the Mesopotamian suzerainty. When it comes to geophysical work in the southern Levant, GPR is the method most often employed; very few magnetic gradiometry surveys have been attempted. The geophysical survey of Busayra, however, highlights the need for multi-method approaches to geophysical work in the region, as the data generated from the magnetic gradiometry survey illustrate significant magnetic contrast between the architecture at Busayra and the surrounding soil, while the GPR varied in success in identifying the same architectural features.

The differences between the results from the two methods can provide insight into the geological and geomorphological properties of the features and soils at the site. This also raises the question of whether or not the ‘empty spaces’ (such as the one seen in the northern portion of survey area C), where little to no contrast can be identified in the current geophysical data, were in fact truly empty. These ‘empty spaces’ invite the application of other non-intrusive methods at Busayra to test the effectiveness of the survey methods discussed here.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the University of California, Berkeley, with the help of a SPARC Award. The SPARC programme is based at CAST at the University of Arkansas, and is funded by a generous grant from the National Science Foundation (awards 1321443 and 1519660). Thanks also go to Jordan’s Department of Antiquities and the American Center of Oriental Research for their support.

References

- Aerial Photographic Archive of Archaeology in the Middle East (APAAME). Archive accessible from: www.humanities.uwa.edu.au/research/cah/aerial-archaeology (accessed 10 March 2016).

- BIENKOWSKI, P. 2002. Busayra: excavations by Crystal-M. Bennett 1971–1980 (British Academy, Monographs in Archaeology 13). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Authors

* Author for correspondence.

- Stephanie H. Brown*

250 Barrows Hall, Near Eastern Studies Department, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94707, USA (Email: brown.stephanie85@berkeley.edu) - Benjamin W. Porter

Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, 103 Kroeber Hall, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94707, USA (Email: bwporter@berkeley.edu) - Katie Simon

Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies, JBHT 304, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72701, USA (Email: katie@cast.uark.edu) - Christine Markussen

Initiative College for Archaeological Prospection, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria; 2800 S Highland Mesa Road, Apartment 18-106, Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA (Email: cmarkussen@gmail.com) - Andrew T. Wilson

School of Computer Science, Bangor University, Dean Street, Bangor, Gwynedd LL57 1UT, UK (Email: a.wilson@bangor.ac.uk)

Cite this article

Cite this article