Nahal Efe: a multi-period prehistoric site in the north-eastern Negev

Introduction

The ‘Nahal Efe project’ is a Spanish-Israeli joint initiative launched in 2015. Its aim is to improve understanding of the settlement history of the Negev during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), a period when small-scale mobile foraging groups exploited both highlands and lowlands, probably on a seasonal basis (e.g. Bar-Yosef 1984; Goring-Morris 1993). The project examines human-environment interaction in arid regions, and the regional impact, if any, of major early Holocene environmental fluctuations and rapid climate changes in the development of settlement patterns and subsistence economies during the Middle and Late PPNB (c. tenth millennium cal BP).

Nahal Efe

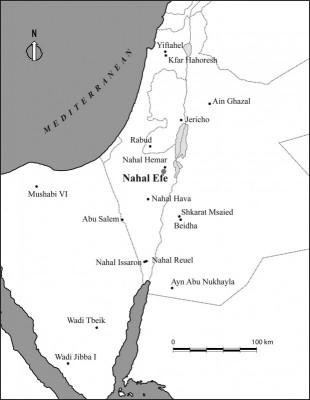

The archaeological site of Nahal Efe is located in the north-eastern Negev highlands, 11km east of Dimona, close to the edge of the Judean Desert (Figure 1). The site is situated at approximately 320m asl on a moderate hillslope on the left bank of the Nahal Efe stream, a tributary of Nahal Hemar (WGS84, 31°04” 43”N and 35°09”02”E). The site was discovered during the 1990s, and, although unexcavated until the current project, it has often been treated in the literature as a PPNB site (e.g. Goring-Morris & Belfer-Cohen 2013) or base camp (e.g. Gubenko et al. 2009).

Fieldwork

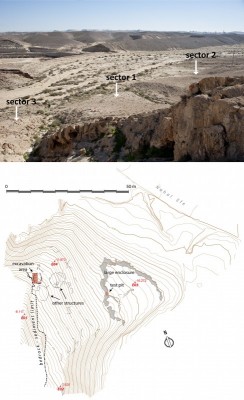

The first excavations took place in December 2015, with the aim of determining the dates and extent of activity there. The site is divided by two small gullies into three sectors with no direct stratigraphic connections between them (Figure 2).

Fieldwork concentrated in sector 1, which constitutes the main area of the archaeological site (around 2000m2). Archaeological material is relatively abundant on the surface, mostly flint artefacts but also fragments of grinding stones, stone bowls and a few pottery sherds. The eastern part, downslope and closer to the riverbed, is dominated by a large enclosure or terrace wall(s) displaying internal divisions. The central and western parts (uphill) display a series of circular and semi-circular stone structures visible on the surface (in some cases superposed and/or overlapping one another) that resemble the characteristic beehive architecture documented at a series of PPNB sites located in the Negev, such as Nahal Hava I (Birkenfeld & Goring-Morris 2013), Nahal Issaron (Carmi et al. 1994) and Nahal Reuel (Ronen et al. 2001).

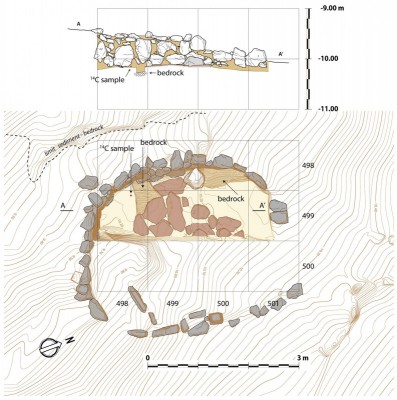

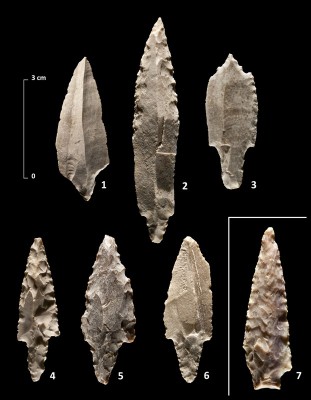

Limited fieldwork was conducted in one of the circular structures, located on the top north-western part of the sector (Figure 3). The structure seems to have been half dug into the hillside. It is in a very good state of preservation, with the walls surviving to a height of about 0.8m on the less-eroded, western side (Figure 4). The wall was built with upright, flat limestone slabs, with a series of smaller stones on top. The floor was partially paved with flat limestone slabs. The structure was filled by the partial collapse of the stone wall and by loess sediment. Flint artefacts (flakes and blades) were relatively abundant. In clear contrast to the layers associated with the abandonment and collapse of the structure, a 100mm-thick layer with abundant macrobotanical remains was found over the floor, which is interpreted as an accumulation derived from repeated activities performed during the occupation of the building. This layer yielded a Jericho point, a small number of undiagnostic flint artefacts, four hammerstones and abundant charcoals (Figure 5). All the above-mentioned data leads to a preliminary interpretation of the structure as a single-phased habitation building. One of the charcoals (identified as Retama raetam) was sampled for radiocarbon dating at the Weizmann Institute of Science, giving a date in the first half of the tenth millennium cal BP (10 000–9650 cal BP, 95.4% probability), and thus Middle PPNB.

The large enclosure downslope is composed of a continuous, thick, irregular wall constructed with three to four courses of medium- to large-sized limestone blocks. A 1m2 test pit adjacent to the inner part of the western wall of the enclosure yielded a few flint artefacts and a sherd of pottery.

In sector 2, surface material is very scarce, limited to some flint flakes. In contrast, architectural remains are noticeable with two tumulus-like structures each composed of two concentric stone rings (the outer rings measure around 7–8m in diameter) (Figure 6). These structures are very different from the building excavated in sector 1.

A rapid inspection of sector 3 revealed the remains of a collapsed wall associated with a very limited number of undiagnostic flint artefacts.

Conclusions

The fieldwork carried out during this first season has confirmed Nahal Efe as a major PPNB site. The extent of the site, the degree of conservation of the architectural remains and the rich archaeobotanical record are unique in the region. These features indicate the great potential of Nahal Efe to improve understanding of the settlement history of the north-eastern Negev Highlands and the southern Judean Desert during the Neolithic, prior to the onset of a pastoral mode of subsistence. It will also enable an appraisal of the potential impact of early Holocene climate instability in the region and an evaluation of its effects on population dynamics during the Neolithic.

Furthermore, the 2015 field season has also identified rich architectural remains (the large enclosure in sector 1 and the two tumulus-like structures in sector 2) that seem to correspond to a significantly later occupation, which could tentatively be attributed to the Chalcolithic and/or Bronze Age. In this sense, Nahal Efe constitutes a multi-period prehistoric site that offers the opportunity to characterise the evolution of prehistoric settlement in the region across a wide chronological span.

Acknowledgements

Fieldwork at Nahal Efe was conducted under the licence of the Israel Antiquities Authority G-85/2015. The project has received financial and logistical support from the Generalitat de Catalunya (Research Group SAPPO/GRAMPO-2014-SGR-1248), Centre de Recherche Français à Jérusalem, Universidad de Cantabria and the Israel Antiquities Authority. We are also grateful to Emil Aladjem, Kyle Mknabb and Gregory Seri for their assistance during the fieldwork.

References

- BAR-YOSEF, O. 1984. Seasonality among Neolithic hunter-gatherers in southern Sinai, in J. Clutton-Brock & C. Grigson (ed.) Animals and archaeology, volume 3: early herders and their flocks: 145–60. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- BIRKENFELD, M. & A.N. GORING-MORRIS. 2013. Nahal Hava: a PPNB campsite and Epipalaeolithic occupation in the central Negev highlands, Israel, in F. Borrell, J.J. Ibáñez & M. Molist (ed.) Stone tools in transition: from hunter-gatherers to farming societies in the Near East: 73–85. Bellaterra: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

- CARMI, I., D. SEGAL, A.N. GORING-MORRIS & A. GOPHER. 1994. Dating the prehistoric site Nahal Issaron in the southern Negev, Israel. Radiocarbon 36: 391–98.

- GORING-MORRIS, A.N. 1993. From foraging to herding in the Negev and Sinai: the early to late Neolithic transition. Paléorient 19: 65–89. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/paleo.1993.4584

- GORING-MORRIS, A.N. & A. BELFER-COHEN. 2013. The southern Levant (Cisjordan) during the Neolithic period, in M.L. Steiner & A.E. Killebrew (ed.) The Oxford handbook of the archaeology of the Levant c. 8000–332 BCE: 147–69. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- GUBENKO, N., O. BARZILAI & H. KHALAILY. 2009. Rabud: a Pre-Pottery Neolithic B site south of Hebron. Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society 39: 69–80.

- RONEN, A., S. MILSTEIN, M. LAMDAN, J.C. VOGEL, H.K. MIENIS & S. ILANI. 2001. Nahal Reuel, a MPPNB site in the Negev, Israel. Quartär 51–52: 115–56.

Authors

* Author for correspondence.

- Ferran Borrell*

Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistóricas de Cantabria, Universidad de Cantabria, Avenida de los Castros s/n, 39005, Santander, Spain (Email: silmarils1000@hotmail.com) - Elisabetta Boaretto

Kimmel Center for Archaeological Science, Weizmann Institute of Science, P.O. Box 26, Rehovot 76100, Israel (Email: elisabetta.boaretto@weizmann.ac.il) - Valentina Caracuta

Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Palaecology, Department of Cultural Heritage, University of Salento, Via Dalmazio Birago 64, 73100 Lecce, Italy (Email: valentina.caracuta@unisalento.it) - Eli Cohen-Sasson

Department of Bible, Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Studies, Ben Gurion University, P.O. Box 653, Beer Sheva 8410501, Israel (Email: eli.timna@gmail.com) - Ron Lavi

8 Dan Street, Modi’in 7173161, Israel (Email: ronlavi@gmail.com) - Ronit Lupu

Inspection Department, Israel Antiquities Authority, P.O. Box 586, Jerusalem 91004, Israel (Email: kivaiko@yahoo.com) - Luís Teira

Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistóricas de Cantabria, Universidad de Cantabria, Avenida de los Castros s/n, 39005, Santander, Spain (Email: luis.teira@unican.es) - Jacob Vardi

Prehistoric branch, Excavations Survey and Research Division, Israel Antiquities Authority, P.O. Box 586, Jerusalem 91004, Israel (Email: jacobv@israntique.org.il)

Cite this article

Cite this article