SERGE CASSEN. Exercice de stèle: une archéologie des pierres dressées, réflexion autour des menhirs de Carnac. 158 pages, 20 illustrations, 19 colour plates. 2009. Paris: Errance; 978-2-8772-394-7 paperback €29.

Review by Alison Sheridan

National Museums Scotland, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK

(Email: a.sheridan@nms.ac.uk)

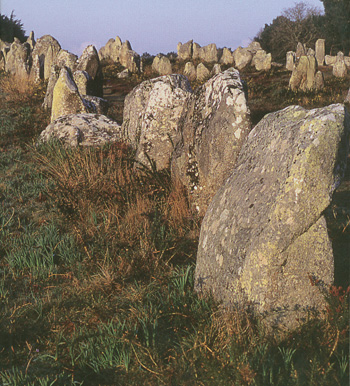

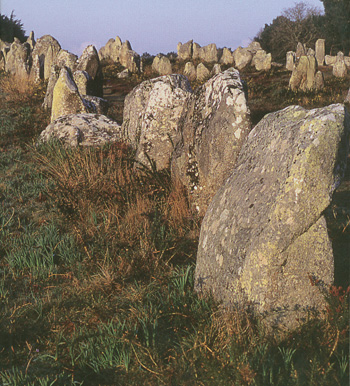

Exercice de stele — the title a reference to Raymond Queneau's Exercices de style in which the same story is recounted 99 times — is an extended essay exploring ways of approaching and understanding the standing stones of the Morbihan region of Brittany that have fascinated its author, the distinguished French archaeologist Serge Cassen, since his childhood. Cassen makes it clear from the beginning that this is neither a conventional archaeological account of our current state of knowledge, nor a popularist guide to these well-known monuments. Rather, it is an exercise in epistemology, directed towards addressing the simple but profound question of 'Why were these stones erected?'

The book sets out to create 'a kind of model' that can be tested — a model that draws on imagination as well as on reason — and it is structured in four sections headed 'the object of the research', 'the subject of the research', 'the nature of the research' and 'the practice of the research'. It starts by challenging and deconstructing the commonly-held interpretation of the Carnac and other alignments as temples. Along the way it explores the semantics and 'architecturologic' of megalithic architecture, showing how the erection of standing stones was a powerful way of inscribing meaning in the landscape, through their permanence, their height, their arrangement, their adornment with powerful symbols, etc. In essence, the model which is developed sees these massive erections — both single standing stones and more complex settings — as the product of a time of change during the first half of the fifth millennium BC, when novelties drawn from contact with farmers were being adopted and integrated within the world-view of the fishers, hunters and gatherers living on the southern coast of Brittany. Turning conventional perceptions of the stone alignments on their head (or rather, re-viewing the stones at 90 degrees), Cassen offers a seductive view of these monuments as constituting a barrieragainst the supernatural dangers of the sea (just as some American servicemen, during World War II, allegedly thought that the Carnac alignments were real defences against German seaborne tanks). Following the shape of the coast, rather than any astronomical alignment, these lines of uprights both threaten (the forces of danger, such as sea monsters) and protect (their builders). The designs pecked into some of the stones reinforce this message, with phallic imagery (as seen, for example, on a stele at Mane Rutual) being intimidatory and apotropaic in nature. The model goes much further than this, suggesting a binary opposition in the imagery on individual stones, and proposing that elements of traditional mythology — most notably the importance of the crow/raven — are echoed in these stones. The section in which he proposes ways of testing his model (in 'La pratique de la recherche') is rich in practical suggestions, and highlights just how much more remains to be recorded and learned from these monuments. For example, the idea that the breakage of the large stelae such as the Grand Menhir was caused by natural tremors is persuasive, and Cassen's suggestion of replicating experimentally the process using scale models is a sensible one.

Cassen is well known for his stimulating and challenging approach to understanding the megalithic constructions of Brittany. It was he, for instance, who encouraged us to see the 'hache-charrue' design on some standing stones as a representation of a sperm whale; who pioneered innovative techniques of recording and mapping monuments; who discovered stone alignments that had been drowned by the rising sea; who investigated the long-distance contacts of the builders of the gigantic tumulus carnacéens; and who worked with Jean L'Helgouach on the astonishing complex of monuments at Locmariaquer (the definitive publication on which fieldwork is shortly to be published). Cassen draws fruitfully on this experience, and develops concepts that he had launched elsewhere (e.g. in his 2000 volume, Éléments d'architecture), to enrich his discourse. He also draws heavily on French and German philosophical writing (among many other sources) and, unlike many anglophone archaeologists, he really knows his Baudrillard from his Bachelard.

This is a demanding book — and one for whose comprehension Tinaig Clodoré-Tissot's new (2009) and otherwise-handy Dictionary of archaeological terms will not be of much help. Self-consciously brilliant in its dazzling display of scholarship and culture, bien sûr, and at times over-optimistic (e.g. in proposing the testing of his model worldwide, p. 118-9), it is, nevertheless, a rewarding and entertaining read.