Review Article

Mesolithic Europe: diversity in uniformity¹

Leendert P. Louwe Kooijmans

Formerly Faculty of Archaeology,

University of Leiden, The Netherlands

(Email: louwekooijmans@planet.nl)

¹ With apologies to Pieter Modderman (1988)

Books Reviewed

GEOFF BAILEY & PENNY SPIKINS (ed.). Mesolithic Europe. xviii+468 pages, 94 illustrations, 27 tables. 2008. Cambridge & New York: Cambridge University Press; 978-0-521-85503-7 hardback £55 & $95.

SINÉAD MCCARTEAN, RICK SCHULTING, GRAEME WARREN & PETER WOODMAN (ed.). Mesolithic horizons. 2 volumes, lx+1007 pages, 688 illustrations. 2009. Oxford: Oxbow; 978-1-84217-311-4 hardback £150.

NYREE FINLAY, SINÉAD MCCARTEAN, NICKY MILNER & CAROLINE WICKHAM-JONES. (ed.). From Bann Flakes to Bushmills (Prehistoric Society Research Paper 1). xxiv+224 pages, 84 illustrations, 23 tables. 2009. Oxford: Oxbow; 978-1-84217-355-8 hardback £35.

CLIVE WADDINGTON & KRISTIAN PEDERSEN. Mesolithic studies in the North Sea Basin and beyond: proceedings of a conference held at Newcastle in 2003. viii+158 pages, 100 illustrations. 2007. Oxford: Oxbow; 978-1-84217-224-7 hardback £48.

TOM CARLSSON. Where the river bends — under the boughs of trees. 380 pages, 59 illustrations. 2008. Stockholm: Riksantikvarieämbetet; 978-91-7209-502-1 hardback £18.

The five volumes on the European Mesolithic reviewed here all appeared within three years. Together they show an increase in the popularity of a period long considered poor and uninteresting. The reviewer is someone who mainly concentrated on the ensuing Neolithic, albeit in a region where earlier traditions remained incorporated in daily life; he started and ended his career with contributions to the Mesolithic, a period in which he has always been greatly interested. This review article offers the views of a 'kindly relative' who agrees with Lars Larsson (in Mesolithic horizons, p. xxi) that: 'A common thread is the hope for a better research connection between those scholars who are dealing with the Mesolithic and those who are researching the Neolithic.'

The five books comprise the proceedings of the huge 'Meso 2005' conference (Mesolithic horizons), three further edited collections (Mesolithic studies in the North Sea Basin, From Bann Flakes to Bushmills and Mesolithic Europe, the latter a comprehensive overview of the research field) and an idiosyncratic monograph on a Swedish site written in English (Where the river bends).

European overview

Mesolithic Europe is a volume of twelve chapters written by highly-qualified authors marshalled by Geoff Bailey and Penny Spikins who contribute an introduction and conclusion. Their aims, stated in the Preface, were 'to bring together a series of regional syntheses of the Mesolithic in different parts of Europe ... and to provide an up-to-date overview of the current state of knowledge, a demonstration of the richness and diversity of the material now available and the various approaches to its study'. They gave their authors strict instructions, asking them to cover: the history of research, definition of the Mesolithic, environment and geography, chronology, technology and subsistence, settlement and social organisation, art and ritual and the nature of the (time) boundaries including the transition to agriculture. A rather ambitious enterprise! Did they succeed? Yes and no. There is a wealth of information from all over the European subcontinent and the book is extremely useful as an orientation to Mesolithic themes and regions, not least because of its impressive (integrated) bibliography of some 1800 titles and a 14-page index. We should, however, not consider it a text-book to be read from the first to the last page, but rather as a source of information to be consulted for quintessential information and references. If I point out some aspects which I would have preferred treated slightly differently, this should not be seen as a criticism of the intrinsic qualities of the book, but as desires not entirely fulfilled. There is some imbalance between the regions covered (e.g. the Iron Gates microregion in contrast to the whole of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine taken together); the same holds for the ratio between authors from British and American institutions (9) and those from the regions themselves (5: Bjerck, Blankholm, Valdeyron, Svoboda and Verhart). Illustrations are similarly patchy: radiocarbon date lists occupy 28 pages and there are 24 site location maps, but very few illustrations of hut plans, burials or other relevant finds. Graphs and tables documenting isotopic and faunal evidence are few and the illustrations are factually rather dull. The result is that the book is sound and thorough but fails to generate enthusiasm for the Mesolithic as a research arena. This was surely not intended by the editors and their contributions help to redress the balance: the first half of the introductory chapter by Penny Spikins and the final chapter by Geoff Bailey give us an admirable and up-to-date thematic overview of the Mesolithic as a whole, as each chapter does for its region. All serious students of European prehistory should have this book on their shelves!

Meso 2005

If the preceding book is the most ambitious of the five, Mesolithic horizons is the most massive. It gives an overview of the Mesolithic too, but this time it showcases current work and inevitably does so in a more kaleidoscopic way. The book contains the contributions to the seventh five-yearly conference on 'The Mesolithic in Europe' which was held in September 2005 in Belfast. For the first time in the history of the conference two volumes were needed, weighing 4.5 kg. The conference was guided by the 'unwritten, fundamental principle [that], where possible, all those who wish to speak should be given an opportunity to speak' (Preface) and that all contributions should also be printed. The result is 1065 pages containing 144 papers written by 192 authors (out of c. 250 participants) from over 20 countries. Apart from the references at the end of each contribution, there is a 'consolidated bibliography' of 88 pages with c. 2500 titles, and a 10-page index. All papers are introduced by a summary, except those in the current research section. They are spread rather unevenly over the study area: 28% concern British or Irish subjects, 26% Scandinavian and 24% southern European themes. Only four contributions each are on Central and Eastern European topics and none deal with the Balkan peninsula, a fact observed by Lars Larsson in his analysis of trends in the conferences over the past 35 years.

The first five papers, representing the conference's plenary sessions, consist of Europe-wide perspectives by five 'old masters': Stefan Kozlowski discusses 'his' topic of geographical differentiation of microliths, Lars Larsson contributes a retrospect, Douglas Price peers (briefly) into the future, Marek Zvelebil takes a (longer) view of the current state of the Mesolithic, especially the concept of the 'Mesolithic', and Peter Woodman considers Ireland's special place (it was after all a Belfast meeting!). The other papers are arranged according to the themes of the conference, in short: postglacial colonisation, mobility, environment, places, regional identities, dwellings, transitions, ritual and social aspects, flint and non-flint technology and finally 'current research'. Each section of 10-15 papers opens with a reflective introduction by the chairperson, thus making an enormous body of material accessible.

Producing these two volumes must have been quite a job and the editors deserve our greatest respect. Criticism would seem ill-mannered, but I shall still permit myself some remarks. First, access to all this knowledge could have been improved by separately indexing the contents pages by author and geography (say, by country). Secondly, a number of comparable studies are found scattered under a variety of headings e.g. mortuary practices under 'ritual' and 'social context', settlement systems under 'places' and 'technology'. This may not have been a problem at the conference, but the volumes would have benefited from some rearranging. The general index alas is of no great help in this respect.

Mesolithic at the edge

From Bann Flakes to Bushmills is a Festschrift in honour of Peter Woodman. It is the first volume in a new series of research papers published by the Prehistoric Society. As with most Festschriften it contains a diversity of papers, but it should come as no surprise that for this laureate the focus is mainly on the Mesolithic and I shall restrict myself to these contributions. Of 21 papers 16 cover either the Mesolithic or the Mesolithic/Neolithic transition and 12 of these deal with either Ireland or Britain (Scotland and Star Carr), while Lars Larsson reports on the renewed research at the spectacular cemetery of Zvejnieki in northern Latvia. The Irish and Scottish papers reveal the research school founded by Peter Woodman, which has populated the 'empty landscapes at the Mesolithic edge of the world' as far north as West Voe in the Shetlands. There are papers on artefact classes, on microregions and raw material acquisition. It is evident that the Mesolithic in these countries at the edge is very resistant to research and that we are very dependent for our view of the period on the rare occasions when dwellings and organic material are preserved. I feel, however, that we should not let ourselves be seduced into fleeing into postmodernism to escape the frustrations of poor flint assemblages on bare rocks, an approach adopted, amongst others, by a paper on 400 (Mesolithic?) flints from 98 'locales' collected on the shores of Lough Allen in Ireland.

Without intending to be unfair to the other contributors, I would like to pay a special tribute to the authors of three 'non-British' papers, who each present excellent and sharp analyses of important topics and major debates: Erik Brinch Petersen & Christopher Meiklejohn who discuss the isotope study of human remains in southern Scandinavia, Douglas Price & Hanna Noe-Nygaard who consider the earliest evidence for domestic cattle and, last but not least, Bill Finlayson who contributes an inspiring and polemic article on the archaeological (mis)use of the concept of 'complex hunter-gatherers' and more generally the use of ethno-analogies in our modelling of past societies. This is a paper that anyone dealing with late foragers and early farmers should read and re-read. The book ends with an index carefully composed by Julie Gardiner.

North Sea central?

Mesolithic studies in the North Sea Basin and beyond contains the papers of a one-day conference in Newcastle, organised because 'it was thought timely to follow up the excavations at Howick ... discussing recent finds from countries surrounding the North Sea Basin', which has been 'a dynamic environment subject to immense change during the Late Quaternary and early Holocene' and because 'The ebb and flow of cultural interactions ... poses an exciting challenge to archaeologists'. These quotes from the introduction sound quite ambitious compared to the content of the volume. Apart from the short introduction there are 15 contributions, 11 of which are on British and two on Scandinavian Mesolithic topics. The southern part of the Basin is not considered.

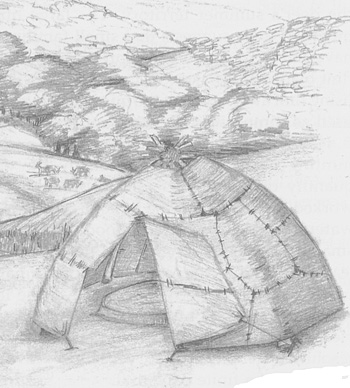

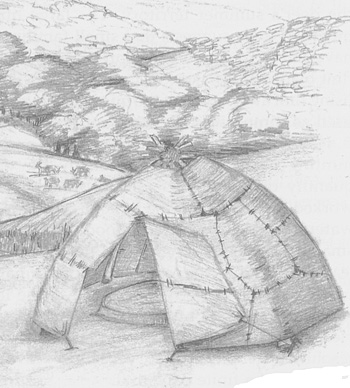

Most prominent is the contribution by Clive Waddington on the spectacular round hut, discovered in an erosion scar on a cliff edge at Howick in Northumberland, dating to the early eighth millennium cal BC. In addition Waddington gives an overview of Mesolithic hut structures and intrasite features in the British Isles, with some references to sites abroad, and proposes a new classification system of sites based on the modes of residency; these may however not be so easily applicable in most real world cases. A hut, in many respects comparable to the 'Mount Sandel type', is the hut from East Barns, East Lothian, Scotland, presented by John Gooder. Both are examples of good state-of-the-art field archaeology.

I regret to say that quite a few of the other papers which report fieldwork are disappointing in their interpretation and/or presentation. What makes Saveock in Cornwall Mesolithic? Are there no doubts or alternatives for the Hawcombe Head clay floor? Do the 14C dates of pine charcoal at Silvercrest really date the post circles 'in an area of predominantly Bronze Age remains'? If so, are we to understand that the two circles are 1100 years apart? And why are the microlithic assemblages at Oliclett not retooling locations at selected points and why 'suggest' and 'believe' so much on the basis of one modest flint assemblage on 'mound A'? For me an 'enculturated landscape' needs more tangible evidence, more than a few artefacts at more or less special places, where they generally are.

Surprisingly no reference is made to the spectacular remote sensing research by the School of Geography and Environmental Sciences at the University of Birmingham (Fitch et al. 2005; now Gaffney et al. 2009, published after the volume reviewed here) or to the Early Mesolithic finds from the North Sea floor itself, such as those from the Brown Bank. Some illustrations could have been designed more carefully and included scale bars and more precise information on the location of sites and trenches. But the book makes knowledge available in a condensed form, knowledge otherwise not easily accessible, especially abroad.

Swedish post-modernism

Tom Carlsson's book is an explicit and emphatically postmodernist reconsideration of his 1999-2003 excavation at Motala-Strandvägen in Östergotland in Sweden, a 90m long and 10-20m wide section of a late Mesolithic riverbank site of unknown extent. An earlier report was published in Swedish by the Riksantikvarieämbetet. The site was discovered and excavated — partly underwater — as a consequence of the construction of a new railway. The site is unique in central Sweden for its preservation of bone implements (c. 50 barbed point fragments) and refuse, allowing that part of the subsistence based on animal resources to be assessed. The excavation also produced 800 hammer stones, over 100 greenstone axes and 180 000 flint and quartz artefacts, two antler punches or pressure flakers and two pieces of decorated bone. Most important in the interpretation ('The home in the world — the world in the home') are two (incomplete) plans of structures: a larger oval one measuring 4 x 8.5m (plan) or 5 x 10m (text) and a smaller one, probably circular, of about 4m (plan) or 5m (text) in diameter. Both are indicated by dark shading on all the plans, although no depression or discolouration is mentioned in the text. A warning is issued to those who are sceptical about these houses: they will have to put up with 'the Mesolithic house syndrome'. Thirty 14C dates are spread between c. 5900 and 4500 cal BC, but the main occupation is considered to date to 5500-5000 BC. Most interesting and really unique are two concentrations of fist-sized pebbles in the muddy bank zone, interpreted as platforms for leister fishing: close to these stones at least 17 broken tips of bone barbed points (Figure 17) were recovered 'in vertical position deep down in the bottom of the river'.

Motala is an important and well-documented site and space does not allow me to criticise details of interpretation. It is only sad that this alternative postmodern approach is confusingly presented, that basic data are difficult to find or not given at all. Above all the 150 000 word-long (!) text would have benefited from being shortened considerably. To my mind, there appears to be a significant imbalance between the lavish presentation of all the arguments on significance and meaning and the exposition of the excavated data.

Some considerations

Data and research strategies, expectations

All these pages offer a distinct picture of Mesolithic research today, the efforts of an extensive research community which comprised over 250 participants at the Belfast meeting. The picture is a mixture of what people do and would like to do, expressed in several forward-looking papers (e.g. by Price, Larsson, Milner & Woodman).

In general, in most regions, Mesolithic evidence is indeed restricted to imperishable (stone and flint) materials in scatters with a restricted spatial and stratigraphic resolution. Research concentrates on technology — typology being out of date — and spatial topics: intrasite patterns, site location, settlement patterns and systems with reference to the environment, raw material acquisition, mobility and territoriality. There is a general dearth of evidence, in the form of dwellings, burials, organic preservation and symbolism, which could offer a more vivid view of society. Despite new discoveries, this appears to be a structural problem for the period. The limits of what is preserved and therefore what is knowable seem to have been reached and research has focused on more of the same, if denser, data sets. Larsson even observes that: 'Some of us are fed up with cemeteries and good preservation, and are eagerly trying to find theories and methods in order to intensify information from imperishable materials' (Mesolithic horizons, p. xxix). That would indeed be one way to a more sophisticated Mesolithic view.

A second element seems to be better dating. There is a distinct preoccupation with 14C dating, however without prospects, so far, for a chronology finer than the three to five phases generally distinguished. Two questions arise: first, whether sharper dates are at present a core issue, given the relatively modest changes in the Mesolithic trajectory; and second, whether we can expect to establish 'duration' with some accuracy on this basis.

Hopes rest on new techniques, such as analyses of aDNA, stable isotopes (Sr, 15N, 13C, O, S ...), microwear, residue, physical anthropology, computer applications, and, on a larger scale, excavation and intensive survey, especially under water. The number of studies dealing with these techniques is, however, quite small in the volumes reviewed here, as are papers on organics, artefactual as well as economic. There still is a gap between wishes and practice.

Postmodernism or anthropology?

While for some more advanced theory might be the way out from the frustration generated by the poverty of the evidence, others escape from reality into postmodern imagination (or should I say 'fantasy'?). If the Mesolithic horizons volumes are representative of the whole, it seems that it is the young northern female researchers that are especially tempted by this approach. Carlsson (p. 305), quoting Julian Thomas states: 'As a consequence of the postmodern outlook ... we know (my emphasis) that modern thought is probably (idem) the worst conceivable ground for interpretations of the Other: in this case, of prehistory and of people of other cultures.' It is my opinion that modern scientific research is the only way to progress and that we have overcome ethnocentrism and the uncritical use of analogies years ago. A phenomenological approach may add value to a rich data set, but cannot replace the lack of basic data. For further reading I suggest consulting Marek Zvelebil in Mesolithic horizons, pp. lii-liii.

Instead our view of Mesolithic society would be improved considerably by the adoption of critical anthropological reflections, like those of Finlayson (quoted above) and Alain Barnard (2002) on the forager mode of thought.

Definition

There is a standing discussion about the continued validity of the concept of a Mesolithic (see Zvelebil in Mesolithic horizons and Milner & Woodman 2005). This is as if biologists would question whether there are mammals. Yes, there are. They are as diverse as bats and giraffes, whales and pygmy shrews, but they certainly have common denominators. Diversity in the Mesolithic is far less pronounced.

For most of us the 'Mesolithic' represents a stage of the postglacial, peopled by foragers and collectors who use a stone technology, defined specifically in Europe. Outside Europe the period is not distinguished as such or is named differently. We should not include the northern hunters up to medieval times, as Marek Zvelebil (in Mesolithic horizons) provocatively proposes. We should keep our periodisation, which is primarily based on artefact characteristics and, exceptionally, on a 'revolution' (for the Mesolithic/Neolithic boundary), not on supposed shared knowledge systems or common cosmologies.

The upper and lower time boundaries of the Mesolithic are essentially diachronous, like all time boundaries of our 'periods', even when we are not able to measure the time differences, and they seemingly are 'horizontal'. The Mesolithic ends where the Neolithic starts and it does not matter that we cannot always pinpoint the upper boundary because of transitional phenomena, like in the Swifterbant situation. The same holds for the lower boundary. We should not include the Hamburgian nor should the Upper Palaeolithic include the Azilien. The Alleröd interlude asks for a flexible and not a dogmatic approach. That we want to include the preceding and following periods in our study is a quite different matter. But factually this is not important, not a core issue.

Uniformity and diversity

The Mesolithic people had much in common. They were foragers and collectors, hunters, gatherers and fishers, concentrating on aquatic resources, living in small groups often in 'persistent places' in use for (many) centuries, all mobile, albeit in different ways. The geographical and climatic variation within Europe is self-evidently a major basis of differentiation: think of the different ways of life between the Mediterranean and the Subarctic, between the Atlantic facade and interior Russia. Some groups may have adopted pottery. They were generally egalitarian, except for a few who may have met the criteria for 'complex hunter-gatherers' sensu NW coast Indians. This is contrary to the opinions collected by Lars Larsson (Mesolithic horizons, p. xxviii) and in agreement with Bill Finlayson's arguments. These 'complex' societies may after all have been restricted to those in the Iron Gate area, perhaps not by accident people living at the frontier of the Neolithic world.

After reading or consulting these 2300-odd pages, I am left with an uneasy feeling of scattered information and of a somewhat blinkered view of the European Mesolithic as a whole. The 'complex and multicoloured tapestry' (Spikins in Mesolithic Europe, p. 6) is stressed more than the common denominators. The highlights shining from a few oases in these publications are in danger of becoming dimmed by the rather meagre evidence in most regions.

So, a future goal may be to gain a greater appreciation of the Mesolithic and do greater justice to these highly successful temperate forager communities. Self-evidently we have to acknowledge and look for differentiation, but I feel that, to complement the regional studies, wider thematic overviews are needed, to bridge the archaeological (semi)deserts and to identify common ground above the differences. To mentions just one aspect, innovations, documented in regions far apart from each other, must also have been part of the outfit of the communities 'in between'. And to appreciate these subtleties, more attention should be paid to the quality of illustration, as is customary for instance in southern Scandinavia (e.g. Andersen 2009).

Finally it is important to restore communication with research communities to the east, regain apparently lost contacts and indeed increase diachronic contacts with the Upper Palaeolithic and the Early Neolithic. By improving our understanding of the transitional stages, we should also be able to better identify the originality of the Mesolithic, its internal dynamics and changes.

References

- ANDERSEN, S.H. 2009. Ronæs Skov. Marinarkæologiske undersøgelser af kystboplads fra Ertebølletid (Jysk Arkæologisk Selskabs Skrifter 64). Højberg: Jysk Arkæologisk Selskab.

- BARNARD, A. 2002. The forager mode of thought, in H. Stewart et al. (ed.) Self — and other — images of hunter-gatherers (Senri Ethnological Studies 60): 5-24. Osaka.

- FITCH, S., K. THOMSON & V. GAFFNEY. 2005. Late Pleistocene and Holocene depositional systems and palaeogeography of the Dogger Bank, North Sea. Quaternary Research 64: 185-96.

- GAFFNEY, V., S. FITCH & D. SMITH 2009. Europe's lost worlds: the rediscovery of Doggerland (CBA Research Report 160). York: Council for British Archaeology.

- MILNER, N. & P. WOODMAN. 2005. Looking into the canon's mouth, in N. Milner & P. Woodman (ed.) Mesolithic studies at the beginning of the 21st century: 1-13. Oxford: Oxbow.

- MODDERMAN, P.J.R. 1988. The Linear Pottery Culture: diversity in uniformity. Berichten van de Rijksdienst voor het Oudheidkundig Bodemonderzoek 38: 63-140.