JEAN CLOTTES Cave art 334 pages, over 300 colour plates. 2008. London: Phaidon; 978-0-7148-4592-0 hardback £45, $90 & £75

JEAN CLOTTES Cave art 334 pages, over 300 colour plates. 2008. London: Phaidon; 978-0-7148-4592-0 hardback £45, $90 & £75

Review by John Coles

Cadbury, Devon, UK

Fifty-five years ago this reviewer walked into the cave of Lascaux - no guide, no supervision - and explored and admired the vivid paintings that most of us know well from numerous books and papers. Lascaux today is not so brilliant due to the serious effects of various polluting agencies. But the thousands of earlier visits included many photographers whose work is ever-more important in the documentation of the artistry not only of Lascaux but also of many cavern walls bearing paintings and engravings of Late Glacial times. Here in this book, called simply Cave Art, the paramount French specialist of the subject has assembled over 300 pictures, both old and new, of images painted and engraved, arranged in a general chronological system which some may dispute.

At first glance, Cave Art looks like a coffee-table tome, large, thick and heavy, full of colour and captions, with seemingly little in the way of discursive text. But this book is more than an ornament: in its Introduction the author sets out his structural approach and his opinion on a wide variety of important subjects, starting out with chronology and retaining the classic West European sequence of Aurignacian, Gravettian, Solutrean and Magdalenian. There follows a comment on the distribution of sites, predominantly in France and Spain, but also incorporating 'a minor engraved site in England (Creswell Crags)' as well as comparable small sites elsewhere in western Europe. Here is where the book's title is convenient but misleading, as contemporary open-air sites are included; few of these generally receive the prominence of the decorated caves. The technologies of painting, engraving and carving are briefly addressed and then the author identifies the principal 'themes' in the art, the word 'themes' perhaps overgenerous as he seems more realistically to be listing individual subjects - geometrics, herbivores, humans, and indeterminates including composites. To comprehend a 'theme' within the repertoire needs more on matters such as context, position, association, size and quality, in this reviewer's opinion. And here again the book's Cave Art concept is extended to include mobiliary art, well-illustrated among the pictures of wall-based paintings and engravings. The mobiliary art is crucially important as support for the author's chronological scheme noted below.

The author then lists three areas of research that concern him - themes and techniques, cultural and environmental contexts, and ethnological comparisons - in the expectation that these will aid our quest for a meaning behind it all. Here it must be said that both geographical width and chronological depth act to defeat the emergence of any demonstrable 'truths', and the three approaches are not fully integrated, nor ever could have been for such a subject. The author does his best to avoid dogmatism in his final introductory pages where a historical approach is adopted for the ever-beguiling and never-conclusive subject of Interpretations.

The various theories, from Art for Art through Sympathetic Magic to Structuralist concepts are replaced now, in the author's view, by Shamanic Religion. Anticipating some opposition to this last-named interpretive approach, the author makes two statements. The first is his acceptance that 'some of the observations and arguments put forward in previous hypotheses are still valid'; the second is that 'many researchers today ...mistrust... any type of interpretation at all'. There can be few prehistorians who come to the caves and shelters who will not have some opinion or theory to account for certain aspects of the artistic representations, and the search for a universal truth must surely be misguided. A large area, a vast time-frame, substantial environmental alterations, these and more suggest variation, amendment, expansion, hiatus, perhaps disputes and confrontations , that would certainly alter any overall initial concept of social practice that originally inspired and initiated the processes of what we appreciate as 'artistry'. The author believes that 'the structure of Palaeolithic thinking and the manner in which they manifested themselves barely changed until the upheaval at the end of the ice age'. That is one opinion.

The bulk of Cave Art consists of single and double-page spreads of photographs of painted and engraved images, chronologically-arranged into three Ages, and terminated here by a short assemblage of rock art from around the world and of post-Pleistocene age; this last section could have been omitted as the pictures can do little more than emphasise the fragmentation of the grand Ice Age concepts, with no examination of how, why or when such late manifestations of cave, shelter, open-air and mobiliary art appeared.

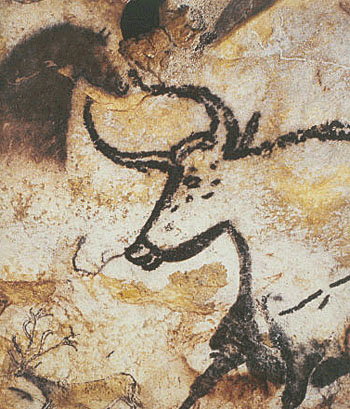

Each of the three main chronologically-arranged sections consists simply and without overall comment of photographs of those images believed to date appropriately and to express the character and identities of the figures, some barely discernable or incomplete, others dramatic and almost individually identifiable within their specific grouping; the Chauvet horseheads are an obvious example, and a pity that the same cannot be exposed here for the Altamira bison.

The selection of photographs for the book has been based very much upon imagery, the particular animal or less-identifiable symbol, rather than upon groupings and contextual associations. There are welcome exceptions, particularly for the author's key and defining sites: Chauvet and Gargas for 'The Age of Chauvet 35 000-22 000 years ago', Lascaux and Cosquer for 'The Age of Lascaux 22 000-17 000 years ago', and Niaux for 'The End of the Ice Age 17 000-11 000 years ago'. Readers of Antiquity will be aware of the dispute concerning the radiocarbon dates for the Chauvet art; the matter is not argued anew in this book, although the author acknowledges the differing opinions. The five type-sites are well-illustrated in the book, with some photographs of walls, ceilings and crevices. But no such contextual view appears for sites such as Altamira, Font de Gaume and Rouffignac. For this last site, a brief mention of the original controversy over the authenticity of much of the imagery is dismissive of those whose doubts were once fiercely expressed. And for this reviewer, the several bison and horses of Le Portel figured here can hardly reflect the intricacy of the multi-channelled cavern, in which long ago he dropped and broke his lamp, alone, and then waited in deep silence and all-enveloping blackness until a rescuing torch was brought along the passageway, briefly illuminating the black horses that seemingly bucked and danced about on the walls; this is surely the way to observe and reflect upon the images, their place and their power.

Cave Art is certainly an impressive and attractive book, and would look well on my coffee-table, if I had one, and it deserves a prominent place among the ever-growing range of monographs on Ice Age art. But it is surely time, now, for a more conceptual and analytical approach to this body of archaeological evidence.