RONALD HUTTON. Blood & mistletoe: the history of the Druids in Britain. xiv+492 pages. 2009. London: Yale University Press; 978-0-300-14485-7 £30.

RONALD HUTTON. Blood & mistletoe: the history of the Druids in Britain. xiv+492 pages. 2009. London: Yale University Press; 978-0-300-14485-7 £30.

Review by Miranda Aldhouse-Green

School of History and Archaeology, Cardiff University, UK

(Email: Aldhouse-GreenMJ@cardiff.ac.uk)

Despite its title, this book is not about the Druids, well not about the real ones, anyway. Its dramatis personae are not the ancient Druids of Caesar, Pliny and Lucan's texts, but rather the extraordinary imaginings of early modern British antiquarians, not least their mythologies concerning Stonehenge. As a study of Druidomania between the sixteenth and twenty-first centuries, Hutton's volume is a tour de force. The author is at his very best in his sheer breadth and depth of scholarly research of this period, and his work is laced with elegance and humour.

In the first chapter, Hutton reviews the source material — the ancient literature of Graeco-Roman authors that first propelled a group of elite politico-religious leaders into the imaginations of their peers. He rightly points out that no archaeological evidence points unequivocally to the existence of Druids, and since they were operating within a Gallo-British context of the later centuries BC that was almost entirely non-literate, assumes that absence is to be expected. (One odd omission in this opening section is acknowledgement of Nora Chadwick's The Druids, an important summary of the Classical literature published in 1966). The following chapters explore the fascinating world of English, Scottish, Welsh — and to a lesser extent Irish — antiquarianism, and the pages are stalked by such gigantic luminaries of 'modern' Druidism as Aubrey, Stukeley, Iolo Morganwg, George Watson Reid and many others. Close attention is paid to the rise of early professional archaeology and the way monuments such as Stonehenge acted as conduits for connections between antiquaries and archaeologists.

Hutton is particularly illuminating on the flurry of secret societies that sprang up in London and elsewhere during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I was overjoyed to find that — in such a very male world of exclusive Druid clubs — 1853 saw the foundation of the Noble Order of Female Druids, and that in 1911 concern was raised over the false beards worn by members of the Ancient Order of Druids for fear that they might harbour TB bacilli! His identification of 'modern' Druids as a rallying point for patriotism within Britain is of the utmost importance.

Nevertheless there are weaknesses. It is a pity that such a splendid critique of the hijacking of Druids by successive generations of antiquaries and Neo-Druids seems to be built upon the sands of doubt that the 'real' Druids of the remote past ever existed. Hutton appears to suggest that such authors as Caesar quite possibly invented Druids but why should he have? And why did so many others of his broad contemporaries speak of them as well? Inventions in Caesar's Commentaries could easily have been laid bare by those fellow officers, like Quintus Cicero, who served with him in Gaul. And the lack of specific archaeological verification for ancient Druids provides no grounds for their dismissal as a figment of collective Classical imagination. Similarly, the absence of emic literature ratifying the Druids' existence does not constitute evidence for their fictionality: prehistory, by its very nature, has no literature but no one doubts the reality of the human past from the Palaeolithic to the Iron Age. Caesar's Druids are a rare instance of a named interest group, and we should think hard before turning our backs on them because of suspicions of fairy-tale journalism. A second issue concerns the absence of any attempt at theorisation. On his own admittance, Hutton eschews theoretical approaches, but what rich pickings are to be had by a theoretical perspective on those wonderful antiquarian minds that stride the stage of Blood and mistletoe. Thirdly, in seeking to debunk some of the purveyors of Druidomania and, in particular, the spurious linkage with Stonehenge, Hutton fails to acknowledge that one reason for lumping together Druids and ancient monuments was that the absence of precise scientific methods of dating made it difficult for genuinely scholarly antiquarians to perceive a long time-frame for the British and European past.

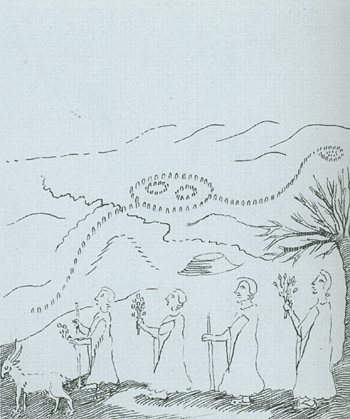

There are also some defects of a practical nature. First, the absence of a bibliography is astonishing in a volume of this length and scholarly depth. Yes, the book is well referenced, but endnotes, however full, are no substitute for a good old-fashioned, alphabetically-ordered bibliography. The illustrations are well-chosen but they are not put to work for the book: there is little or no cross-referencing between text and images. Rather than engage in lengthy descriptions of the physiognomies of John Toland, William Stukely, William Wordsworth or John Lubbock, why not point the reader to their portraits?

The book is too long and contains some padding. Each chapter presents a densely written narrative that occasionally (as in the two chapters on Welsh Druidomania) loses its way. I suspect that the text would be clearer and more accessible were it to include some subheadings. But the book is an overwhelmingly positive contribution to scholarship. With apologies to Hutton for plagiarising a phrase of his own, this study definitely falls into the category of a 'palace of learning' (p. 73), although I am far from certain that it 'does what it says on the tin'.