K.R.U. Todd: a forgotten personality in the study of Indian prehistory

Introduction

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, significant contributions to the study of India’s prehistory were made by the enthusiastic and dedicated work of, amongst others, geologists, planters and military personnel. While the exemplary contributions of R.B. Foote (Pappu 2008) and M.C. Burkitt (Smith 2013) have been recognised, others have received sparse attention. Killingworth Richard Utten Todd, better known as K.R.U. Todd (Figure 1), is one such neglected personality in the history of Indian archaeology. Todd’s best-known publications concern his research into the stratigraphy and prehistoric cultural sequence of Bombay (modern Mumbai), which are still quoted today.

Todd was born in 1905. He joined the Royal Indian Navy as a Sub-Lieutenant, rising to the post of Commander. During World War II, he led the H.M.I.S Jumna from Chittagong to Akyab for the Burma Operations. Despite these duties, he pursued his archaeological interests in both South Asia and England.

Around Bombay

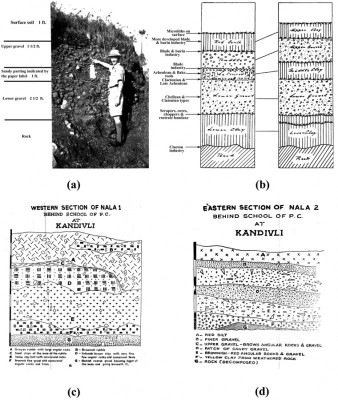

His classic research papers on the prehistory of Bombay (Todd 1932, 1939, 1950) document the discovery and establishment of a prehistoric cultural sequence in the region. Todd’s (1932) initial surveys around Worli led to the discovery of what he termed ‘Chellean’ artefacts including handaxes. He appears to have followed on from the work of G.E. Carter (Indian Civil Service) who reported early Palaeolithic tools here. Discussing the classic site of Khandivli, Todd (1939) identified a stratigraphic section showing a continuous cultural sequence (Figure 2). He noted handaxes, comparing these with those of the ‘Madras industries’ in modern Tamil Nadu (Pappu 2007). He also discovered what he termed ‘Mousterian’ and ‘Aurignacian’ tools at Colaba and Worli respectively. At various other localities around Bombay, Todd discovered microliths and compared them with those he discovered at Calicut (Kerala) (Todd 1932: 42). He also discovered fossils at Kasu Shoal (Todd 1932: 38) and Khandivli (Todd 1939: 261). In 1935, he excavated at Marve (Bombay), discovering microliths, pot sherds and hearths (Todd 1939). Todd (1932: 35, 39) wrote that tools found in Back Bay reclamation material came from Worli Hill, later accepting E.R. Perry’s (Indian Civil Service) observation that this was partly from Khandivli (Todd 1939: 257).

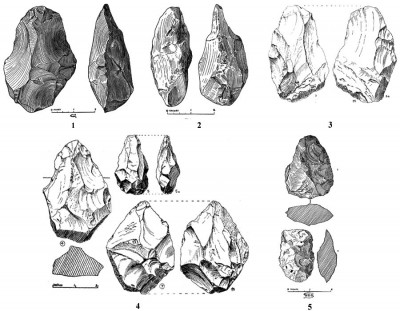

This region was later investigated by others (Kalapesi 1946; Malik 1959; Sankalia 1959–60; Guzder 1975). Malik agreed with Todd’s stratigraphy but could not find ‘Clactonian’, ‘Chellean-Clactonian’ or Late Acheulean tools. Sankalia (1959–60) termed Todd’s research as ‘classic’, owing to the discovery of a continuous sequence, unknown at that point in time in South Asia. Sankalia, a leading contemporary figure in Indian prehistory, however, disagreed with Todd’s stratigraphy of Khandivli both in terms of field observations and interpretation, and in terms of tool types and the formation of the deposits noted. Important in this respect is that Sankalia could not find any handaxes in Khandivli while illustrations by M.C. Burkitt’s wife in Todd’s article (1932: 42) clearly indicate that some tools were indeed bifaces (Figure 3).

Microliths and Mysore

Todd’s understanding of microliths is notable, as micro-burins collected by him and examined by J.G.D. Clark (Todd 1950: 6) were possibly the first to be reported in India. Todd (1948: 30) was also one of the earliest to point out the association of microlithic tools with medium- to heavy-duty tools.

By 1948, Todd’s understanding had deepened, looking at microliths from a chronological as well as a regional perspective. This is seen from his work at Mysore, in southern India, which has received far less prominence, despite his observations of microliths at Jalahalli, capped by a horizon with ceramics. Placing Jalahalli in a chronological framework, he pointed out that the association of microliths with medium to heavy tools was absent in southern India and Ceylon but present in Bombay and northern India (Todd 1948). On this basis he tried to differentiate between early and late microlithic phases and placed Bombay and Jalahalli in early and late phases respectively. He considered burins to be chronological markers, as they were invariably found along with flake-blades and continuing right up to the microlithic industries. He concluded that these microliths predated the Iron Age of southern India (Todd 1948). The contradictions with H.D. Sankalia continued here, disagreeing with the latter’s typology of microlithic assemblages in western India. Todd attempted to situate this Indian data in a global context and proposed theories on population dispersals along the coast and compared this with the ‘strandloopers’ of South Africa (Todd 1950: 10).

The Soan

Todd’s work predates de Terra and Paterson’s (1939) classic research in the Soan. Following observations by Wadia (1928) and reports of stray Palaeolithic finds from the Sohan (Soan) Valley in 1880, Todd undertook a survey at Pindi Gheb, the only note of which to be found is in the Punjab Gazetteers (Garbett 1930: 20–21). This note is referred to by de Terra and Paterson (1939: 293). He later collaborated with T.T. Paterson on a joint unpublished paper of 1947 on the flint assemblage from the Lyari River, Karachi. He also exchanged ideas with M.C. Burkitt, A.S. Barnes and J. Reid Moir (Todd 1932).

In England

E.S. Wood (1952), writing in memory of Todd, describes his work in England, which comprised a small excavation in a medieval flint mine at East Horsley and a wider survey of the Neolithic sites of west Surrey in 1949, but Todd died in 1950 before he could complete his work there.

His premature demise may explain why his role in the vibrant study of Indian prehistory during the 1930s and 1940s has been neglected. His contribution lies in his discovery of stratified deposits, the establishment of a cultural sequence, surveys in areas untouched by fellow researchers, attempts to establish chronological and regional schemes and to link assemblages in India with those of West Asia and Africa. His work, although brief, created a base for future researchers of Indian prehistory.

Acknowledgements

I thank Professor Shanti Pappu and Professor S.N. Rajguru for help and advice on this topic. I thank staff of the Pitt Rivers Museum, Surrey Archaeological Society and National Archives, UK, for their help with this study.

References

- DE TERRA, H. & T.T. PATERSON. 1939. Studies on the Ice Age in India and associated human cultures. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- GARBETT, C.C. 1930. District and states gazetteers of the undivided Punjab (prior to Independence), Volume 1. Delhi: B.R.

- GUZDER, S.J. 1975. Quaternary environment and Stone Age cultures of the Konkan, coastal Maharashtra, India. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Poona University.

- KALAPESI, A.S. 1946. Stone implements of the Palaeolithic age from Kandivli, Bombay. Journal of the Gujarat Research Society 8(2–3): 123–24.

- MALIK, S.C. 1959. Stone Age industries of the Bombay and Satara districts. Baroda: Faculty of Arts, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda.

- PAPPU, S. 2007. Changing trends in the study of a Palaeolithic site in India: a century of research at Attirampakkam, in M.D. Petraglia & B. Allchin (ed.) The evolution and history of human populations in South Asia: 121–35. Dordrecht: Springer.

– 2008. Prehistoric antiquities and personal lives: the untold story of Robert Bruce Foote. Man & Environment 33(1): 30–50. - SANKALIA, H.D. 1959–60. Stone Age cultures of Bombay—a re-appraisal. Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bombay (new series) 34–35: 120–31.

- SMITH, P.J. 2013. The roots of an intellectual empire: Miles Burkitt, ‘knowledge travel’ and archaeology in early-twentieth-century Europe. Antiquity 86(338) Project Gallery. Available at: http://antiquity.ac.uk/projgall/pjsmith338/ (accessed 2 March 2014).

- TODD, K.R.U. 1932. Prehistoric man round Bombay. Prehistoric Society of East Anglia 8(3): 35–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0958841800026351

– 1939. Palaeolithic industries of Bombay. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 69(2): 257–72. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2844392

– 1948. A microlithic industry of eastern Mysore. Man 48: 28–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2792452

– 1950. The microlithic industries of Bombay. Ancient India 6: 4–16. - TODD, K.R.U. & T.T. PATERSON. 1947. A flint microlithic industry from Karachi, India. Unpublished manuscript.

- WADIA, D.N. 1928. The geology of Poonch State (Kashmir and adjacent portions of the Punjab). Memoirs of Geological Survey of India 51: 185–370.

- WOOD, E.S. 1952. Neolithic sites in west Surrey (with a note on a medieval flint mine at East Horsley). Surrey Archaeological Collections 52: 11–23.

Author

- Tejal Ruikar

Deccan College, Pune – 411006, India (Email: truikar@gmail.com)

Cite this article

Cite this article