Ice Age villagers of the Levant: renewed excavations at the Natufian site of Wadi Hammeh 27, Jordan

Introduction

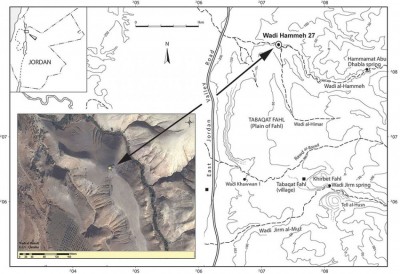

The Natufian period (13 000–10 300 cal BC) in the Levant is considered a crucial juncture in human settlement history because it marks the transition between the mobile hunter-gatherers of earlier Epipalaeolithic phases (20 000–13 000 cal BC) and the sedentary, agrarian villagers of the Early Neolithic (10 300–8300 cal BC; Bar-Yosef 2011). Wadi Hammeh 27 (c. 12 000–12 500 cal BC) in Jordan (Figure 1) is one of only a few known Early Natufian open-air, ‘base-camp’ type settlements (Bar-Yosef & Goren 1973: 67; Henry 1989: 219). It features large and complex pre-Neolithic buildings, a series of well-preserved artefact caches and activity areas, and a rich corpus of art. It is representative of the first sites where communities not only invested considerable energy in building residences in the form of substantial huts on stone foundations, but also refurbished and revisited them for generations—over hundreds and even thousands of years. The Natufian has been claimed as an example of pre-agricultural sedentism, but the length and frequency of its habitations remain unclear. One issue is that, for the majority of sites, long-term occupation of a single locale by hunter-gatherers would deplete food resources (cf. Munro 2004).

These concerns are the focus of a new La Trobe University project (Edwards 2014) entitled ‘Ice Age villagers of the Levant: sedentism and social connections in the Natufian period’, directed by the author and co-directed by Louise Shewan (Monash University/University of Warwick) and John Webb (La Trobe University). In order to achieve the project’s aims, the new excavations are intent on stripping away more of the overlying deposits of phases 2 and 3 at Wadi Hammeh 27 to expose the basal travertine layer (phase 4), where human burials are situated in rock-cut pits (Webb & Edwards 2013). Through the use of strontium analysis of human teeth to estimate the length of residential occupations and the frequency of residential shifts, the project seeks to advance our understanding of how Natufian communities founded the earliest villages in the Jordan Valley around 12 500 cal BC.

The first series of excavations, conducted in the 1980s, focused on the site’s uppermost deposits in phase 1 (Edwards 2013). A small sounding (XX F sondage) made at that time also demonstrated occupational continuity between the superimposed phases and the community memory of a sub-site burial by the building of successive cairns and other markers. These practices are among the first expressions of household tenure in the Middle East, or indeed anywhere in the world. Earle (2000) has suggested that the creation of boundaries in architectural space, including the internal demarcation of buildings by walls and other features, marks one of the indicators of property tenure in the archaeological record.

The 2014 excavations

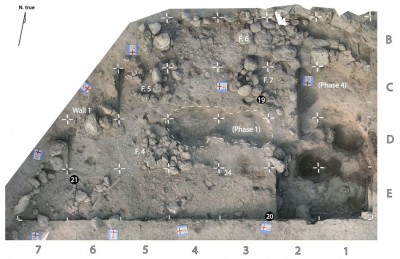

The clearance in 2014 of the phase 2 occupation at Wadi Hammeh 27 under structure 1 (Figure 2) brought to light further examples of inter-generational continuity. For example, feature 7 (square C3), a double-coursed stone ring, is a predecessor to a version of the same feature that continued in use in the overlying phase 1 (Edwards 2013: 73). Feature 4 (square D5) is an oblong stone platform that extends east to square D4 and south into squares C4 and C5. It is truncated by the pit in the north-east corner of square D5. A flat stone is placed at the centre of the stone group, and the feature may have functioned as a post-support, as did several similar features in phase 1 (Edwards 2013: 71). The pit that cuts the feature was itself capped by a roughly rectangular stone platform in phase 1. Square E6 yielded a dense agglomeration of finds (Figure 3), including a zoomorphic basaltic pestle (RN 140049), a phalliform figurine (RN 140225), a basaltic shaft-straightener (RN 140047) and a basaltic handstone (RN 140048). The clustering of materials here reflects a similar concentration in the overlying phase 1 near the light, where structure 1 opened to the west.

The first series of excavations yielded numerous artefact clusters and caches of raw materials (Edwards & Hardy-Smith 2013: 105). Artefact clusters 1–17 occurred in phase 1 contexts, and artefact cluster 18 was found in phase 2 (in the plot XX F sondage). The recent season yielded three additional clusters on the phase 2 floor (Figure 2). Artefact cluster 19 comprised a pair of large flint blades nearly 10cm long, an unusually large size for Wadi Hammeh 27; artefact cluster 20 consisted of three lightly reduced and apparently heat-treated flint cores, and two limestone cobbles; artefact cluster 21 (Figure 3) included a cache of 138 dentalium (Antalis sp.) fragments overlying a pair of retouched blade tools, including a Helwan retouched awl.

New art pieces

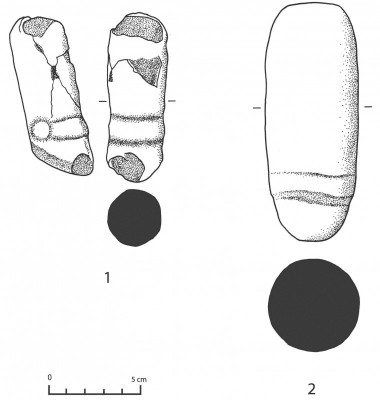

The 2014 season also produced several important artefacts, including some with close parallels to items found at the dawn of research into the Natufian culture nearly a century ago. Of the basaltic artefacts, the most notable finds were two diminutive items (Figure 4); the first, a zoomorphic pestle (RN140049), and the second, a phalliform basaltic pestle (RN140053). The key decorative features of RN 140049 are a raised band circumscribing the shaft near the distal end and an obliquely shaped terminus. In combination, the features suggest an ungulate hoof. The piece finds several Early Natufian parallels in objects from El Wad Cave at Mount Carmel (Garrod & Bate 1937: pl. XV.4), and Hayonim Cave in western Galilee (Belfer-Cohen 1991: fig. 7: 1, 3 & 5). The distal end of RN 140053 features a raised band circumscribing the shaft and at its end the piece is lightly grooved, conveying the impression of a phallic object. The rich square, E6, also yielded a large phalliform limestone figurine (RN 140225). The piece was complete but cracked in situ, and repaired as three conjoinable fragments (Figure 5). A white colouration caps the proximal end of the piece, whereas the rest of the object is light to dark grey. In order to highlight the proximal cap, an area of the piece down the right lateral margin had been reduced by pecking, emphasising the white terminus above it.

The most distinctive find of the season, also from square E6, was a carved and incised bone animal head (RN 140226; Figure 6). It is evidently the terminal piece of a larger object such as a sickle. Although badly damaged and calcined by burning, the rendering of an ungulate animal, probably a gazelle, is compelling. The piece has parallels with objects from Kebara Cave (Turville-Petre 1932) and El Wad Cave (Garrod & Bate 1937: pl. XIII.3). Together, the animal head and the zoomorphic pestle strengthen the links between Wadi Hammeh 27, lying east of the Jordan, and key Natufian settlements to its west.

Acknowledgements

The project is supported by Australian Research Council Discovery Project grant DP140101049; the fieldwork was undertaken courtesy of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan and the support of La Trobe University.

References

- BAR-YOSEF, O. 2011. Climatic fluctuations and early farming in West and East Asia. Current Anthropology 52/S4: 175–93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/659784

- BAR-YOSEF, O. & N. GOREN. 1973.Natufian remains in Hayonim Cave. Paléorient 1: 49–68. http://dx.doi.org/10.3406/paleo.1973.899

- BELFER-COHEN, A. 1991. Art items from layer B, Hayonim Cave: a case study of art in a Natufian context, in O. Bar-Yosef & F.R. Valla (ed.) The Natufian culture in the Levant: 569–88. Ann Arbor (MI): International Monographs in Prehistory.

- EARLE, T. 2000. Archaeology, property and prehistory. Annual Review of Anthropology 29: 39–60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.29.1.39

- EDWARDS, P.C. 2013. Architecture and settlement plan, in P.C. Edwards (ed.) Wadi Hammeh 27: an Early Natufian settlement at Pella in Jordan: 65–94. Leiden: Brill.

– 2014. The earliest village people: past work and future prospects at the Natufian site of Wadi Hammeh 27 in Jordan. Near Eastern Archaeology Bulletin 57: 7–9. - EDWARDS, P.C. & T. HARDY-SMITH. 2013. Artefact distributions and activity areas, in P.C. Edwards (ed.) Wadi Hammeh 27: an Early Natufian settlement at Pella in Jordan: 95–120. Leiden: Brill.

- GARROD, D.A.E. & D.M.A. BATE. 1937. The Stone Age of Mount Carmel 1. Oxford: Clarendon.

- HENRY, D.O. 1989. From foraging to agriculture: the Levant at the end of the Ice Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- MUNRO, N. 2004. Hunting pressure and occupation intensity in the Natufian. Current Anthropology 45 (Supplement): S5–33. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/422084

- TURVILLE-PETRE, F. 1932. Excavations in the Mugharet El-Kebarah. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 62: 271–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2843958

- WEBB, S. & P.C. EDWARDS. 2013. The human skeletal remains and their context, in P.C. Edwards (ed.) Wadi Hammeh 27: an Early Natufian settlement at Pella in Jordan: 367–82. Leiden: Brill.

Author

- Phillip C. Edwards

Department of Archaeology & History, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria 3086, Australia (Email: p.edwards@latrobe.edu.au)

Cite this article

Cite this article