Thinking outside the plaza: ritual practices in Preclassic Maya residential groups at Ceibal, Guatemala

Introduction

Recent excavations of residential groups outside the ceremonial epicentre of Ceibal, Guatemala, have revealed new insights into Maya social organisation during the Preclassic (c. 1000–50 BC) and Protoclassic (c. 50 BC–AD 250) periods. Many scholars have focused on the peripheries of Maya centres to understand dynamic relationships among different segments of society (e.g. Yaeger 2003). The study of ritual practice is key, as ritual creates a sense of group cohesion while facilitating the development of social hierarchies (Turner 1969, 1974; Bell 1992). Research conducted in Ceibal’s core indicates that ritual was integral to early community building (Inomata et al. 2013). Evidence from outlying groups furthermore suggests that peripheral populations had intimate knowledge of Ceibal’s public rituals and played an active role in shaping the community.

Ceibal is a lowland Maya centre located along the Río Pasión in the Department of Petén, Guatemala (Figure 1). Ceibal was occupied between 1000 BC and AD 950, and appears to have been an important centre during the Preclassic and Terminal Classic (c. AD 830–950) periods. The site was first excavated by Adams (1963) and then by the Harvard Seibal Archaeological Project in the 1960s (Willey et al. 1975). During the Harvard project, Tourtellot (1988) conducted a survey of the site’s peripheries. Since 2005, the Ceibal-Petexbatún Archaeological Project, directed by Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan, has continued excavations in the site centre (Group A) to investigate the site’s early foundation and its relationship to non-Maya societies during the Preclassic period (Inomata et al. 2013).

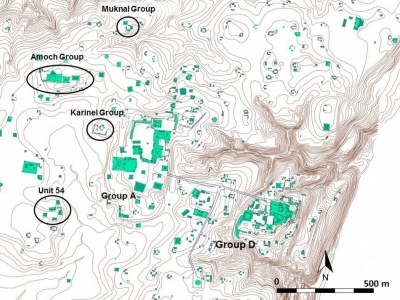

More recently, building on Tourtellot’s research, we have begun systematic and extensive excavations of various residential groups outside Group A (Figure 2). One of our goals is to understand how the relationships between Ceibal’s core and periphery were maintained and negotiated through time. Like most Maya polities, the centralised control of economic activities at Ceibal appears to have been limited (e.g. Rice 1987; Demarest 1992; Triadan 2000; cf. Chase & Chase 2001). Rather, research suggests that populations were integrated through a common ideology that was centred on elites and royals who assumed the role of religious specialists in the epicentre (Ringle 1999; Inomata 2006). This ideology was expressed in public rituals carried out in the Central Plaza. Our data indicate that outlying populations actively participated in the process of creating and sustaining these ritual practices.

This report focuses on findings from the Karinel Group and the Amoch Group, where we recovered evidence of rituals similar to those carried out in Ceibal’s public centre. The Karinel Group (Platform 47-Base) is a large residential platform located 160m west of the Central Plaza. The Amoch Group (Str. 1, Str. 2 and Unit 4E-14) is a minor temple group located 250m north-west of Group A (see Figure 2).

Early Middle Preclassic Period: Burial 132

The Karinel Group was occupied by about 850 BC, during the Real-Xe 2 ceramic phase (Sabloff 1975; Inomata et al. 2013). One of the most interesting discoveries in 2012 was a large burial that contained Real-Xe 3 (c. 800–700 BC) vessels (Figure 3). Burial 132 was placed in a bulbous intrusion in the bedrock. It included the skeletons of two adults and seven complete vessels: four plates (types Abelino Red and Yalmanchac Impressed) and three jars (type Palma Daub) (Figure 4). Inside one of the jars were the bones of an infant.

Burial 132 shares some characteristics with Burial 136, a Real-Xe 3 burial of an adult male excavated in the Central Plaza by Flory Pinzón. According to bioarchaeologist Juan Manuel Palomo, one of the adults in Burial 132 and the individual in Burial 136 underwent tabular-erect cranial modification, the style popular among the Olmec (Palomo 2012: 12–14). Burial 136 contained four ceramic vessels, which were similar to those of Burial 132.

Late Preclassic Period: Burial 147 and Monument 2

Monument 2, a Late Preclassic uncarved limestone altar, was discovered in an excavation on the central axis of Structure 1 in the Amoch Group. It is associated with multiple construction episodes, starting at the beginning of the Cantutse-Chicanel phase (c.400–50 BC), and was eventually incorporated into the façade of a pyramidal structure (Figure 5). The monument was completely covered by another structure at the end of the Late Preclassic.

In an intrusion underneath the monument, the residents placed a large Sierra Red vessel with a plate over its mouth (Figure 6). A child burial (Burial 147) was placed inside. Treatment of the remains before deposition is consistent with human sacrifice. This offering closely resembles another excavated by Flory Pinzón in the Central Plaza (Burial 127), and similar large Sierra Red vessels have been documented in ritual contexts elsewhere at Ceibal. Ceramic evidence suggests that the monument was dedicated during the Cantutse-Chicanel 1 phase (c. 400–350 BC).

Protoclassic Period: Cache 159

During the early Protoclassic (c. 50 BC–AD 50), the residents of the Karinel Group placed a large rectangular intrusion in front of Structure 47. At the bedrock, they deposited Cache 159: 19 complete bowls (types Achiotes Unslipped and Sierra Red) in two levels, some lip-to-lip, along with small, round, flat stone artefacts (Figure 7). Like the vessels in similar Protoclassic caches in the Central Plaza, the bowls are poorly fired, probably created for ritual deposition. Higher up in the intrusion, we found a burial of a child, apparently deposited as an offering. Based on the similarities between Cache 159 and caches in the Central Plaza, it is likely that the residents of the Karinel Group were involved in Ceibal’s public ceremonies. Cache 159 shows a connection between public and domestic rituals.

Conclusions

Evidence from the Karinel Group and the Amoch Group suggests that during the Preclassic and Protoclassic periods, people residing on the outskirts of the ceremonial epicentre had access to specialised ritual knowledge and performed rituals similar to those carried out in the Central Plaza. These specialists probably participated in the creation of Ceibal’s public rituals, rather than merely emulating them. Although outlying residential groups were sufficiently independent to perform their own large-scale ceremonies, the community was integrated through shared ritual practices, which were centred on elites residing in Group A. Overall, this research indicates that the process of developing such practices was not linear, but rather that religious ideas and practices were fluid and negotiable, particularly in loosely centralised societies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Instituto de Antropología e Historia, the Alphawood Foundation, the Tinker Foundation, the School of Anthropology at the University of Arizona, Takeshi Inomata, Daniela Triadan, and all of the researchers who have worked at Ceibal.

References

- ADAMS, R.E.W. 1963. Seibal, Peten: una secuencia cerámica preliminar y un nuevo mapa. Estudios de Cultura Maya 3: 85–96.

- BELL, C. 1992. Ritual theory, ritual practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- CHASE, A.F. & D.Z. CHASE. 2001. Ancient Maya causeways and site organization at Caracol, Belize. Ancient Mesoamerica 12: 273–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0956536101121097

- DEMAREST, A.A. 1992. Ideology in ancient Maya cultural evolution: the dynamics of galactic polities, in A.A. Demarest & G.W. Conrad (ed.) Ideology and Pre-Columbian civilizations: 135–58. Santa Fe (NM): School of American Research Press.

- INOMATA, T. 2006. Plazas, performers, and spectators: political theaters of the Classic Maya. Current Anthropology 47: 805–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/506279

- INOMATA, T., D. TRIADAN, K. AOYAMA, V. CASTILLO & H. YONENOBU. 2013. Early ceremonial constructions at Ceibal, Guatemala, and the origins of lowland Maya civilization. Science 340: 467–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1234493

- PALOMO, J.M. 2012. Mortuary treatment at the ancient Maya center of Ceibal, Guatemala. Unpublished MA dissertation, University of Arizona.

- RICE, P.M. 1987. Economic change in the lowland Maya Late Classic period, in E.M. Brumfiel & T.K. Earle (ed.) Specialization, exchange, and complex societies: 76–85. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- RINGLE, W. 1999. Preclassic cityscapes: ritual politics among the early lowland Maya, in D.C. Grove & R.A. Joyce (ed.) Social patterns in prehistory: 183–223. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks.

- SABLOFF, J. 1975. Excavations at Seibal, Department of Petén, Guatemala: ceramics (Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology 13.2). Cambridge (MA): Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

- TOURTELLOT, G. 1988. Excavations at Seibal, Department of Petén, Guatemala: peripheral survey and excavation, settlement and community patterns (Memoirs of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology 16.1). Cambridge (MA): Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

- TRIADAN, D. 2000. Elite household subsistence at Aguateca, Guatemala. Mayab 13: 46–56.

- TURNER, V.W. 1969. Humility and hierarchy: the liminality of status elevation and reversal, in V. Turner (ed.) The ritual process: structure and anti-structure: 166–203. Chicago (IL): Aldine. – 1974. Pilgrimages as social process, in V.W. Turner (ed.) Dramas, fields, and metaphors: symbolic action in human society: 166–230. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press.

- WILLEY, G.R., A.L. SMITH, G. TOURTELLOT & I. GRAHAM. 1975. Excavations at Seibal, Department of Petén, Guatemala: no. 1, introduction: the site and its settings (Memoirs of the Peabody Museum 13.1). Cambridge (MA): Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

- YAEGER, J. 2003. Untangling the ties that bind: the city, the countryside, and the nature of Maya urbanism at Xunantunich, Belize, in M.L. Smith (ed.) The social construction of ancient cities: 121–55. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

Authors

- Melissa Burham

School of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0300, USA (Email: meliss10@email.arizona.edu) - Jessica MacLellan

School of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0300, USA (Email: jessmac@email.arizona.edu)

Cite this article

Cite this article