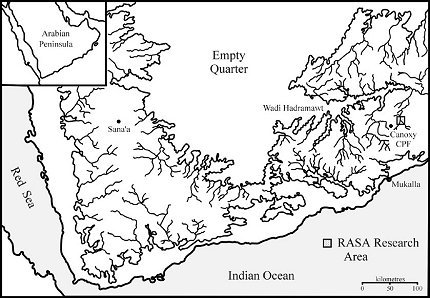

In Southern Arabia’s highland Southern Jol, the RASA Project has documented and dated early water management structures, with important repercussions for prehistoric Arabian resource manipulation and food production. Investigations revealed semi-sedentary occupation by early Holocene people, whose diverse activities included construction of water check dams in the Wadi Sana system (Figure 1, right).

Using high-resolution GPS-GIS survey, RASA documented 13 ancient check dams. They are notoriously difficult to date; Yemen’s examples are no exception. In northern Yemen, early agricultural structures usually have been dated by associated settlement (Ghaleb 1990; Edens et al. 2000). Some water management structures clearly have had no recent use, for they can no longer be reached by surface water or canals. Annual precipitation (50–100 mm) is too low for dry-farming, so for at least the past 5000 years, agriculture in southern Yemen has required water management.

Figure 1: Map of southern Arabia and RASA study sites.

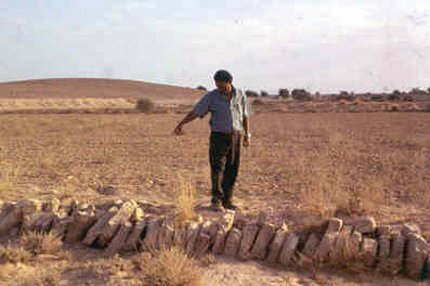

Figure 2: Ancient checkdam constructed of domino-aligned slabs, collapsed during flooding.

In the Wadi Sana and its Wadi Shumlya tributary, check dams lie buried in silts deposited 13,000–5000 years ago. Embedded in a gravel bar deposited more than 5000 years ago, an alignment of imbricated bedrock slabs shows the former contour of a check dam (1998-000-B) (Figure 2, left) destroyed by floods. In construction, tabular slabs of bedrock were taken from a nearby outcrop (50 m), lifted by human hands across a 4-m thick silt bed, and aligned like standing dominoes. Such a structure slows surface water without barring its passage. Modern examples exist nearby, building sediment and nutrients and enhancing soil moisture (Figure 3, below). Flood destruction results in imbricated alignments like the ancient structure, which must postdate the 10,400±4500-year-old optically-stimulated luminescence (OSL)-dated sediment underlying it and predate the 5000-calendar-year-old, in situ Habarut Neolithic knapping floors that cap the gravel bar. Probably this check dam was constructed and maintained by the occupants of slab-lined pit houses radiocarbon dated to c. 6500 years ago (5806±64 BP, AA38544, 4827–4464 BC calibrated at 2Σ, and 5616±84 BP, AA38547, 4674–4261 BC calibrated at 2Σ). These houses represent more substantial occupation than any before or since. The slab-constructed dam is the better-dated but less-preserved of two datable early Holocene check dams in the Wadi Shumlya.

The second check dam (2000-009-1) extended northsouth for 30 m across stream flow. Construction employed larger cobbles from the main channel, probably as double facings for a 1-m wide, rubble-pebble core. Construction and deterioration have been reconstructed through structural analogy with local undated, but fully preserved, check dams (Figure 4, below). Core and upper facings disappeared, probably through ancient flooding. The lowermost cobbles were embedded in aggrading silts (Figure 5, below right). Site 2000-009-1 can be dated through OSL dates (7300±1500 calendar years old) on directly underlying sediment, and near-by sections. Geomorphology and archaeological sites on the surface of the early Holocene silts throughout the Wadi Shumlya indicate that aggradation of sediment occurred prior to the middle-Holocene precipitation decline (Roberts & Wright 1993; Hoelzmann et al, 1998). Fluvial incision and sediment erosion have dominated since about 5000 years ago (4800±60 BP, OS18691, 3636/3544/3548 BC calibrated at 2Σ and 4610±45 BP, OS16958, 3504–3119 BC calibrated at 2Σ on charred layers exposed by fluvial incision). Site 2000-009-1 must be at least as old as the end of early-Holocene sedimentation and probably dates to the phase of semi-sedentary pit-house occupation.

Figure 3: Modern checkdam constructed of domino-aligned slabs.

Figure 4: Ancient checkdam remains have slumped into erosional channel but remain embedded in silts in foreground and rear.

Future research will map and explore the purposes of early water management. While agricultural activities cannot be excluded, the Wadi Sana remains predate known Arabian agricultural systems. Other purposes might include flood control, enhanced grazing, and promoting non-cultigen vegetative growth.

Figure 5: Undated checkdam showing double faced rubble core construction.

Acknowledgements.

Roots of Agriculture in Southern Arabia (RASA) Project includes American, Yemeni, and Canadian scholars generously supported by the National Science Foundation (SBR-9903555, SBR-9711270), Foundation for Exploration and Research on Cultural Origins, CANOXY-YEMEN, American Institute for Yemeni Studies, the University of Minnesota, and The Ohio State University. We also thank the General Organization for Antiquities, Yemen, and its director Dr Yusuf Abdulla, and Dr Ashok Singhi for OSL dates.